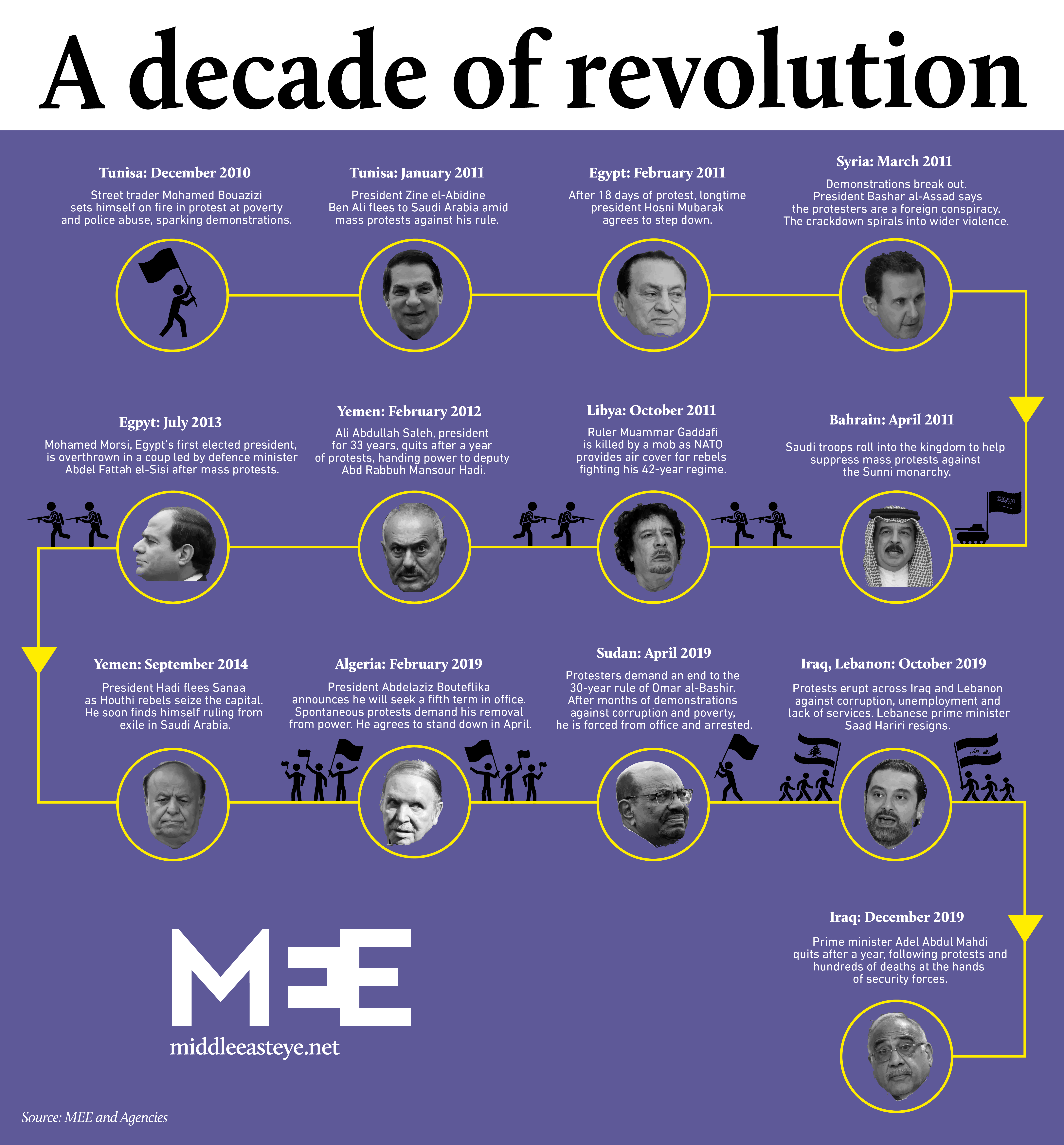

2010-2019: The Middle East's decade of revolution

Clockwise: Sudan's Omar al-Bashir, Libya's Muammar Gaddafi, Algeria's Abdelaziz Bouteflika and Syria's Bashar al-Assad (Illustration by Mohamad Elaasar)

Joe Gill-31 December 2019

New Year 2010: Across the Middle East and North Africa, from Algiers to Damascus, there is a sense of familiarity and continuity.

The Israel-Palestine conflict, the problems of terrorism and economic stagnation, worsened by the global recession, remain intractable. Yet governments, most of them authoritarian and long-standing, appear in full control. The decades-old political order seems immutable. Even the war in Iraq has wound down, and the US-backed government in Baghdad is looking towards elections later in the year.

That a protest in Tunisia in December will spark a wildfire of uprisings that will transform the region is far from most observers’ minds. This is the Middle East. Years change, but the faces of the rulers emblazoned on street posters stay the same.

Then it unfolds: a decade of revolution, civil war and regional conflict. It refuses to subside into a new normal, instead reigniting at the end of the decade to engulf several states that escape it at the decade’s dawn.

While few states are untouched by the rapid emergence of street movements demanding social justice, democracy and accountable government, most Gulf monarchies, Morocco and Jordan avoided the uprisings that swept away ancien regimes and rulers, or led to a bloody, fruitless conclusion.

Yet the view from the palaces of these states, from Riyadh to Abu Dhabi, becomes ever more conscious of the potential threat from fast-moving waves of dissent that can emerge as if from nowhere. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are leading forces of a region-wide counter-revolution, intervening in Egypt, Yemen, Libya and elsewhere.

This is how the decade's revolutions unfolded.

TUNISIA - Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, January 2011

The decade of uprisings began in December 2010 in Sidi Bouzid, with market seller Mohamed Bouaziz’s self-immolation in protest at poverty and injustice.

By mid-January Tunisia’s authoritarian President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali had fled for Saudi Arabia, the first leader to be caught out by the explosion of mass protests. He died there in 2019.

Tunisia’s revolution was the only one this decade that ended in a successful transition to democracy.

Yet the economic deprivation that led to it has worsened: the death of Bouaziz was echoed in November 2019 with the self-immolation of Abdelwaheb Hablani, 25, in Jelma, sparking protests.

The election of political outsider Kais Saied as president in October, alongside a new, fractured parliament, leaves the country’s political parties struggling to form a stable government amid 15 percent unemployment.

EGYPT - Hosni Mubarak, February 2011

Hosni Mubarak, close to the West and Israel, maintained order following the assassination of predecessor Anwar Sadat in 1981. But after a popular uprising began on 25 January 2011, his 30-year rule ended on 11 February.

Mohamed Morsi, the country’s first freely elected leader, ruled briefly before his defence minister Abdel Fatah al-Sisi seized power in July 2013 and crushed all opposition. Morsi died of medical negligence in June 2019 after six years in solitary confinement.

In September 2019, when all thoughts of protest had been quashed through mass repression and hardship, thousands heeded the call of exiled whistleblower Mohamed Ali to take to the streets and protest corruption. Many were arrested.

LIBYA - Muammar Gaddafi, October 2011

The self-styled African revolutionary Muammar Gaddafi fell after 42 years in power in an uprising that followed similar upheavals in neighbouring Tunisia and Egypt.

The turning point in the uprising was the decision by NATO to impose a no-fly zone, which morphed into an air war in support of rebel groups.

In October 2011 Gaddafi died brutally while fleeing, but his death did not mark the beginning of a new order. As Libya divided along east-west and tribal lines, in 2014, Islamic State found a foothold and foreign forces began creeping into the oil-rich country.

Now Khalifa Haftar, an eastern commander once exiled under Gaddafi, is staging a deadly offensive against the UN-recognised government in Tripoli. The two sides have sucked in support from Turkey, the UAE, Sudan, Jordan, Chad and Russia, making Libya's conflict ever more complicated.

BAHRAIN - King Hamad, 1999-

Without the aid of Gulf Arab big brothers the Saudis and the UAE, it is uncertain whether King Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa, a longstanding ally of Britain and the US, would have survived the protests in 2011.

But the majority Shia crowd's demands for reform of the Sunni monarchy were crushed, as Saudi and UAE forces rolled into Manama across the causeway connected to the mainland. Bahrain’s reputation was damaged, but its western allies have become even more supportive. In April 2018 the UK opened its first base in the region for 40 years in the waters off Manama.

YEMEN - Ali Abdullah Saleh, February 2012

During his 33-year reign, Yemeni president Ali Abdullah Saleh created a network of alliances that enabled him to suppress threats and stay in power. Then in 2011 Yemen fell to the unrest sweeping the region and he reluctantly stepped down in February 2012. For many leaders this might have been the end - but not for Saleh.

The Houthis, his old enemies from the Saada mountains, swept into Sanaa in September 2014 and forced out his successor, Saudi-backed Abd Rabbuh Mansour Hadi.

Saleh formed an unlikely alliance with the Houthis and for the next three years his forces opposed the Saudi-UAE military campaign to restore Hadi. But in late 2017 he pivoted towards Saudi Arabia and paid with his life. On 4 December he was killed by the Houthis on the road near Sanaa, ending four decades of corruption and international double dealing. Meanwhile the war continued, dividing the country and creating a devastating humanitarian crisis.

SYRIA - Bashar al-Assad, Syrian civil war, 2011-

Bashar al-Assad had been in power for a little over a decade, after succeeding his father Hafez, when unrest began in Daraa in March 2011. As protests grew, Assad declared them a foreign conspiracy and his regime cracked down, sparking a brutal civil war.

Few expected him to last once the violence escalated, yet by 2015, amid direct Russian backing, the war finally turned against the rebels, who were backed by Turkey, the West and the Gulf Arab states.

The last region controlled by the Islamic State group fell in early 2019: Idlib is the last remaining rebel redoubt after nearly nine years of war and half a million dead, with government bombing intensifying in December.

By the end of the decade, Assad was the only Arab leader outside the Gulf monarchies, Jordan and Morocco, to survive the 2011 protests.

IRAN - Mass protests, 2017-2019

After suffering isolation and sanctions during the populist presidency of Mahmoud Ahmedinejad, Iranians elected moderate candidate Hassan Rouhani in 2013.

He signed the JCPOA nuclear deal with the West and other world powers, with hopes that Iran would benefit from economic growth and trade. But the deal was rejected by Donald Trump on his election in 2016, leading to fresh sanctions.

The harsh consequences of this sparked protests in late 2017 and again, on a larger scale, in late 2019, with hundreds killed by security forces. While conditions in Iran remain grim, the Islamic Republic’s elite appears prepared to take any measures to see off external and internal opposition.

ALGERIA - Abdelaziz Bouteflika, April 2019

After 20 years in power, the frail president Abdelaziz Bouteflika, aged 81, was set to stand for a fifth term. But in February 2019, street protests broke out, demanding he quit.

Bouteflika finally stepped down in April but the movement for change was not assuaged: one by one, members of the old regime were sacked or jailed as the army sought to manage a political transition by removing hated figures, settling scores and trying to prove progress.

A presidential election in December, intended to end the upheaval, was marred by protests and a low turnout as Algerians rejected the polls as coming too early.

After the sudden death in late December of army chief Ahmed Gaid Saleh - regarded as the guardian of the military-dominated political system - the new president, Abdelmadjid Tebboune, has his work cut out opening dialogue with the protest movement, revising the constitution and economic reforms.

SUDAN - Omar al-Bashir, April 2019

Omar Bashir was one of the region’s most canny and ruthless survivors. He came to power after an Islamist-backed coup in 1989, and became an international pariah for hosting Al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden during the '90s and waging a brutal campaign against rebels in Darfur, which led to charges of genocide at the International Criminal Court in 2008.

Bashir came in from the cold in 2017 by making peace with the Gulf monarchies and seeking acceptance from the West. But a determined uprising that began in December 2018 saw him toppled in April and replaced by a transitional civilian-military council.

He was sentenced to two years for corruption in December, with more trials on the way.

IRAQ - 'October revolution' 2019-

By 2010, the Iraq war that was sparked by the US invasion had wound down. Then prime minister Nouri al-Maliki had built up a power base under the new sectarian dispensation, with its inbuilt Shia majority supported by Iran. But with the seizure of Mosul by Islamic State group in June 2014, Maliki lost power to his deputy Haider al-Abadi.

IS was defeated after a bloody four-year military campaign, but within a year, a new threat emerged to the political class: Iraq’s 2019 “October revolution” against endemic corruption, unemployment and the loss of hope among millions.

The protests show no sign of abating, despite hundreds being killed by security forces. Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi, who was only in power for one year, resigned in December, but the demands for fundamental change remain unappeased.

LEBANON - Mass protests, October 2019-

Since the end of Lebanon's 1975-90 civil war, its leaders from the ruling oligarchy have shared power, surviving various crises, the spillover of the conflict in neighbouring Syria, meanwhile failing to provide basic services to the population.

Then, in October 2019, something snapped. Sparked by a tax on mobile phone apps, amid an economic crisis and rising unemployment, unprecedented countrywide protests demanded an end to the corrupt ruling elite, pushing veteran prime minister Saad Hariri to quit.

An uneasy standoff now exists between the ruling elite and the protest movement. A new prime minister, Hassan Diab, a figure from the old establishment, is in place, but there is no end to the movement in sight.