Dolphin researchers say NZ’s proposed protection plan is flawed and misleading

Hector’s dolphins (Cephalorhynchus hectori) are found only in New Zealand. Flickr/Scott Thompson, CC BY-ND

The New Zealand government recently proposed a plan to manage what it considers to be threats to Hector’s dolphins, an endemic species found only in coastal waters. This includes the North Island subspecies Māui dolphin.

Māui dolphins are critically endangered and Hector’s dolphins are endangered. With only an estimated 57 Māui dolphins left, they are literally teetering on the edge of extinction. The population of Hector’s dolphins has declined from 30,000-50,000 to 10,000-15,000 over the past four decades.

The Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) and the Department of Conservation (DOC) released a discussion document which includes a complex range of options aimed at improving protection.

But the proposals reveal two important issues – flawed science and management.

Flawed science

Several problems combine to overestimate the importance of disease and underestimate the importance of bycatch in fishing nets. For many years, MPI and the fishing industry have argued that diseases like toxoplasmosis and brucellosis are the main cause of decline in dolphin populations. This is not shared by New Zealand and international experts, who have been highly sceptical of the evidence. Either way, it is not an argument to ignore dolphin deaths in fishing nets.

Three international experts from the US, UK and Canada examined MPI’s work. They concluded that it is not possible to estimate the number of dolphin deaths from disease, much less claim that this impact is more serious than bycatch. On the other hand, it is easy to obtain an accurate estimate of the number of dolphins dying in fishing nets, as long as enough observers are allocated. MPI has failed to do so. Coverage has been so low that MPI’s estimate of catch rates in trawl fisheries is based on one observed capture.

The MPI model used in the public discussion document (and described in more detail in supporting materials) is complex, and a one-off. It is based on a “habitat model” of dolphin distribution, but fits actual dolphin sightings poorly.

Another problematic aspect of the method is that there is no clear time frame for the “recovery” of dolphin populations to the specified 90% of the unimpacted population size for Hector’s dolphins and 95% for Maui dolphins. This is one of the first things any decision maker would want to know. Would Māui dolphins be held at the current critically endangered population level for another 50 years? If so, this dramatically increases their chance of extinction.

Flawed management options

The second set of problems concerns the management options themselves. These are a complex mix of regulations that differ from one area to another, for gillnets and trawling. They frankly don’t make sense. The International Whaling Commission (IWC) and International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) have recommended banning gillnet and trawl fisheries throughout Māui and Hector’s habitats. MPI’s best option for Māui dolphins comes close to this in the middle of the dolphins’ range, but doesn’t go as far offshore in the southern part of their range.

The South Island options for Hector’s dolphin are much worse. MPI’s approach has been to try to reduce the total number of dolphins killed to just below the level they believe is sustainable. MPI has invented its own method for calculating a sustainable number of dolphin deaths, which is much higher than the well-tested method used in the United States. The next step has been to find areas where the greatest number of deaths can be avoided at the least cost to the fishing industry.

This sounds reasonable, but fixing the problem only in the places where the largest number of dolphins is being killed will have several negative consequences. Experience shows that fishing effort shifts beyond protected areas, merely moving the problem.

For example, MPI’s proposals leave a large gap on the south and east side of Banks Peninsula, in prime dolphin habitat. If the nearby areas are protected, this gap will be fished, and dolphin bycatch will continue unabated. What’s needed is protection of the areas where dolphins live.

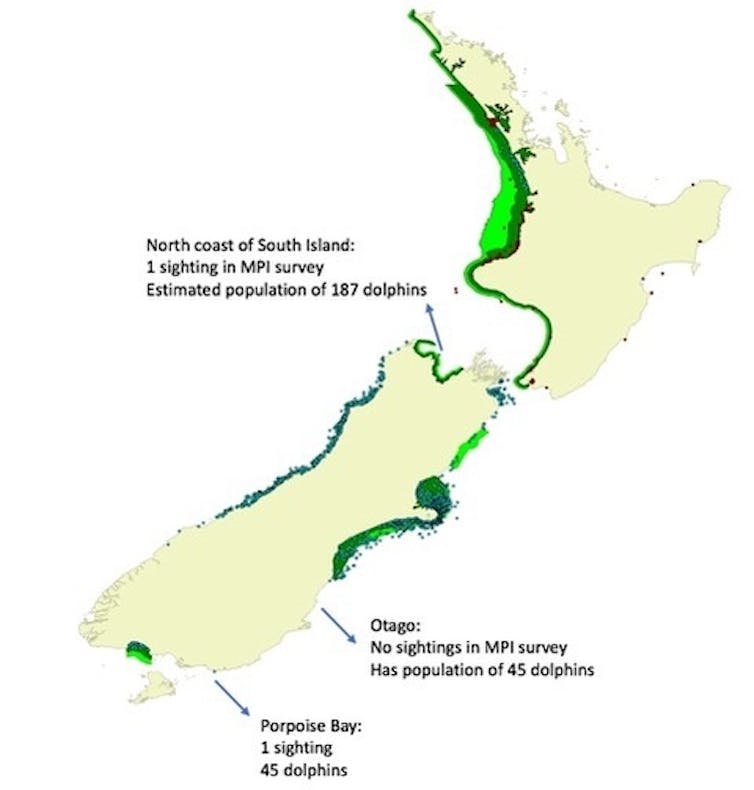

MPI’s focus on reducing the total number of dolphin deaths also ignores the fact that it really matters where those deaths occur. Several Hector’s dolphin populations in the South Island are as small, or smaller, than the Māui dolphin population.

Entanglement deaths have much worse consequences in such small populations, which form a bridge between larger populations. Yet they get no attention in the current options. MPI’s proposals would lead to the depletion of small populations, with increased fragmentation and extinction of local populations.

Only one option

If we want to ensure the long-term survival of these dolphins, there is only one realistic solution: to remove fishing methods that kill dolphinsfrom dolphin habitat. The simple solution is to use only dolphin-safe fishing methods in all waters less than 100 metres deep. This means no gillnets or trawling in harbours and other coastal waters up to the 100 metre depth contour.

There is no need to ban recreational or commercial fishing, but we must make the transition to selective, sustainable fishing methods. These include fish traps, longlines and other hook and line methods. Selective, sustainable fishing methods also use less fuel than trawling and avoid impacts of trawling and gillnets on the broader marine environment.

We also need more observers and more cameras on fishing boats. MPI’s estimate of how many dolphins are dying in fishing nets is almost certainly an under-estimate. It depends heavily on assumptions that are not supported by data.

With observers on only about 2-3% of the inshore fishing boats, the chances of missing bycatch altogether is very high. Low observer coverage also means boats can fish differently on the days when they have an observer aboard (for example, avoiding areas where they have caught dolphins).

We know what works

Despite getting a poor report card from the international expert panel, MPI presented a virtually unmodified analysis to the IWC’s scientific committee last month. The committee identified most of the same issues and concluded it needed more time to decide whether MPI’s approach is fit for purpose. Meanwhile the IWC reiterated its recommendation, which it has been making for eight years, to ban gillnets and trawl fisheries throughout Māui dolphin habitat.

In the meantime, dolphins continue to be killed in fishing. We need to make decisions on the basis of scientific evidence available now. All of the population surveys, including those funded by MPI, show Hector’s and Māui dolphins live in waters less than 100 metres deep.

The best evidence of what works comes from Banks Peninsula, where the dolphins have had partial protection since 1988, and detailed follow-up research. This population was declining at 6% per year before gillnets were banned to four nautical miles offshore and trawling to two nautical miles. Even though there was no management of disease, the rate of population decline has dropped dramatically to less than 1% per year. If disease were a serious problem, the restrictions on gillnets would have made little difference.

A general principle in conservation is that the longer you wait, the more difficult and more expensive it will be to save a species, and the more likely we are to fail.