Sri Lanka’s debt- ridden independence

Sri Lanka needs to drop the debt. Picture (CC - Flickr - Rachel Docherty)

Friday, 1 February 2019

Friday, 1 February 2019On 4 February, Sri Lanka will clock 71 years since we got our independence from the British. Sri Lanka, today, has an estimated $ 87 billion GDP, an economy which is much bigger than what the numbers really reflect. However, the $ 87 billion economy is saddled with unbearable debt. It is estimated that loan repayments between 2019 and 2022 would be around $ 21 billion. The country’s foreign debt is estimated at $ 55 billion. Chinese hold 14% of this debt, Japan accounts for 12%, the Asian Development Bank 14% and the World Bank 11%. Sri Lanka’s debt is 78% of its GDP. This is one of the highest debt-to-GDP ratios in the SAARC and ASEAN region.

During 2010 till 2015, the Chinese pumped in $5 billion worth of loans into building the Mattala Airport, Hambantota port, a coal power plant, a communications tower, and expressways. By 2018, China had loaned Sri Lanka over $ 8 billion. Ironically, for the people of Sri Lanka, some of those investments have been put to unfruitful infrastructure, giving very little return to the people of Sri Lanka. To add to our woes, the current-account deficit continues to worsen. Our debt to be paid out for the next 15 months is around $ 6 billion, according to informed sources. Not very comforting as we celebrate our 71st Independence Day next week.

Unfortunately for Sri Lanka, out of the 225 legislators in the present Sri Lankan Parliament, 94 MPs have not even passed their GCE (O/L) examination, and they don’t really understand what is going on - and those who do are conveniently blind to the reality.

Unfortunately for Sri Lanka, out of the 225 legislators in the present Sri Lankan Parliament, 94 MPs have not even passed their GCE (O/L) examination, and they don’t really understand what is going on - and those who do are conveniently blind to the reality.Debt repayments

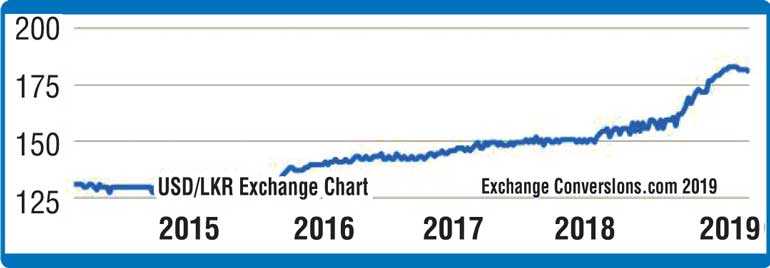

In 2019, the Sri Lankan rupee reached an all-time high of 182.80 in January, and recovered marginally. The prognosis going forward for Sri Lanka is certainly challenging, but can very well be managed, as articulated by business tycoon Dhammika Perera recently on a TV program. According to market sources, Sri Lanka has paid back a $ 1.2 billion international sovereign bond this month by dipping into its foreign exchange reserves, after attempts to raise funds from the international bond market did not fully materialise. Sri Lanka’s economic woes in 2018, in some ways, was aggravated by a self-inflicted political crisis.

A constitutional stunt by President Maithripala Sirisena towards the end of 2018 precipitated a major political crisis. The President first dismissed the Prime Minister in his all-party Government and replaced him with Mahinda Rajapaksa, who failed to get a parliamentary majority and had to step down. Secondly, the President dissolved Parliament, which was subsequently dismissed by the Supreme Court. The two top ratings agencies, Fitch and Standard & Poor, swiftly downgraded Sri Lanka, raising the cost of international borrowing overnight. The country also saw around $ 900 million move out from the stock and bond markets overseas because of the political instability. The tourism sector was the worst hit, due to cancellation of bookings during the peak season.

The Sri Lankan rupee in 2018 deprecated around 15% against the dollar, largely due to a poor economic performance, global political unrest, rising US interest rates, and also due to political turmoil. The largest part of the country’s foreign loan portfolio is today in dollar-denominated international sovereign bonds, estimated to be nearly 50% of the total debt. This is certainly a challenge, given the possibility of further interest rates rises in the US, which could push debt payments even higher.

Way forward

The Government therefore must do more to strengthen the capital account, through attracting FDIs and increasing exports, both of which are under severe stress. There is now a need for steady dollar revenue to flow in to help pay up the dollar debt. This government still enjoys goodwill in the world. Therefore it is up to them to leverage on those advantages to kick start the economy.

Technically, there is a drop in exports from 33% of gross domestic product 20 years ago to 13% currently. The International Monetary Fund has agreed to review the suspended program. According to State media, IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde said: “The IMF remains ready to support the Sri Lankan authorities in their endeavors and an IMF team is scheduled to visit Colombo in mid-February to resume program discussions.”

Today, Sri Lanka’s biggest lenders include the China Development Bank, the Governments of Japan and India, as well as development institutions like the Asian Development Bank and World Bank. Sri Lanka, however, is slowly turning to key Asian allies for financial support to manage the balance of payment crisis. According to market sources, the Government is in discussions with India and China to meet any unprecedented foreign debt obligations. The Reserve Bank of India had agreed this month to provide a $400 million currency swap facility to the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. The Bank of China is meanwhile reported to have offered a $300 million loan. The only real sign of hope for Sri Lanka, is that the Bank of China and the Reserve Bank of India, given Sri Lanka’s geographical importance, is showing increasing interest to scale up their support and could very well become Sri Lanka’s lender of last resort.

Meanwhile, the Government must devise a plan in the shortest possible time to attract FDI, get some serious grants and boost exports. Sri Lanka, unfortunately, has a history of putting the cart before the horse.

(The writer is a thought leader)