Samanalun, Godayas and Our Words

PASAN JAYASINGHE-12/01/2018

When I first heard the word samanalaya used, it was not directed at me. And yet, it was. It was so innocuous – someone said that a name for some team we were part of sounded like a name that butterflies would use, and that we wouldn’t want that, oh no.

For a split second, I was completely lost. The second that followed, when it finally clicked, was one of warm bemusement – what an adorable name for a slur, I thought. It was only when everyone else started laughing with polite smirks that reality kicked in. Immediately, I started going through the motions. Regulating the body – posture, voice, hands – while joining in on the laughter, to give nothing, absolutely nothing away.

This ritual is second nature to my kind, practiced daily. We live in a perpetual state of hyper awareness, both constantly monitoring ourselves and observing those around us for reaction. Most of us have incredible peripheral vision. Maybe unlike real butterflies.

The closest word to samanalaya in English I can think of, fairy, can’t fully capture the belittling levity the word has in Sinhala. The thing is, it is a harmless word. Even when deliberately used in offence, it’s for amusement rather than outright hatred. Because if you really want to cause hurt, there’s a wealth of other words in Sinhala which all sound worse. It’s a lyrical language; in the same way it thickens emotion, it can intensify spite.

Something that may be difficult to understand, however, is that it is never about the one word, or its use just one time. Samanalaya is a signifier and trigger, in all senses of the word. It heightens the hyper-awareness, sets off the rituals, and lets us know exactly who we are and what our place is in the scheme of things. In that sense, a single word becomes a stand in for experience and feeling and reaction all rolled into one.

Such reactions are not limited to being queer, of course. The same internal negotiations are made against similar words by women, minorities and marginalised people of all kinds every day. But queerness is, or can be, a set of identities that are largely internal and not immediately visible (though not always), which means that there is always more to hide.

All of this sounds dramatic but I assure you it really isn’t. It’s so automatic that it doesn’t even register anymore. That is perhaps the most terrifying mercy.

–

When the President used the word samanalaya, it was not directed at me. And yet, it was. I went through the same cycle. Incomprehension, followed by a light chuckle. Reality only kicked in when he paused suggestively, and the approving rumble of the crowd followed, and the camera cut to his new, old friends roaring in laughter. And even though I was watching the speech alone, I could feel my body already initiating the ritual.

Afterwards, what I couldn’t help thinking about was not about President Sirisena or myself but about the fact that there were surely butterflies among that crowd, too. (Yes, even butterflies are complicated enough to be in a crowd like that). Perhaps they were engaging the ritual much more rigorously. What might it really have been like to stand there, the body engaging the motions without thought like an instinctual survival mechanism, against that thunder? A violent kind of safety.

There’s much that can be said about being queer in Sri Lanka. The shunning by our families; the struggles in employment and education; in accessing healthcare services and the law; the effect of criminalisation that runs effortlessly across every layer of society and then through our skin. But despite all these things, it is perhaps the words that end up mattering most in the moment. Because how quickly and ruthlessly they guide everyone’s behaviours. This isn’t about the President, but he only had to say the word that Monday afternoon for our realities to come into sharp, eyewatering focus.

–

A friend I had at school was from just outside Matara. He was a scholarship kid like me, but because he was from outstation he had to stay the school’s hostel. It was a double burden. I only realised how much so when, after a few meetings of the Broadcasting Club – one of those pointless extra-curricular clubs that only seem to exist in Colombo schools – I quizzed him about why he wasn’t speaking up as much. He replied shyly, a hand scratching the back of his neck, that he didn’t want to sound like a godaya. As we held laminated cards with snippets of school news bulletins in front of us to practice speaking properly, his was one of the silent voices. After a while, he stopped coming altogether.

I think I partly got him then, starting to become familiar myself with the intricacies of not giving yourself away. I understood him more fully over the succeeding years, when the vigorous hierarchy of Sri Lankan society asserted itself swiftly over our school. There were the kids who made it through easier than others: the ones who could speak English better, the ones from the Families, the ones who were familiar and comfortable with the dynamics of Colombo or who could learn fast enough. And then there were the kids who didn’t, among whose number would inevitably be the godayas.

We all know how to not be a godaya. How to speak, who to speak to, how to inflect and how to nod your head so your point gets across effortlessly, soundlessly. On paper, these motions may seem dizzying, arbitrary, but after a lifetime of following them, it comes automatically. A merciful terror, but how they’d be intimidating to an eleven year old boy from Kumbalgama.

–

In the reactions to the President’s cataclysmic actions since a month ago, a common refrain has been casting him as a clueless gamarala (farmer), a godaya who wouldn’t know better. Some have taken this further, the gam kabaragoya (water monitor lizard) who couldn’t help himself, or most caustically, the ‘Polonnaruwa Gorakaya’.

The thing about these slights is that they, too, are not really about the President. After all, he hasn’t been a gamarala for a good four decades. Instead, they’re a rebuke against the kind of people he represents. It’s a convenient shorthand for saying, deliberately or not, that some people just shouldn’t be involved in the Important Things: the business of government, running the economy, Democracy. They should just stick to what they know in their villages. After all, no one really tells the Prime Minister – nor for that matter the finance ministers holding up that fuel pricing formula for the benefit of the uneducated with comical glee – to go back to Colombo 7.

We don’t talk about class enough in Sri Lanka. Not just about how the circumstances and wealth we’re born into determine the rest of our lives, but about how the markers of class haunt our lives forever. Being branded a godaya is not just a slur. It’s a stamp of who you are and what you can amount to in a devastatingly permanent sense. Being reminded of that reality by those who’ll never really experience it – could anything be more casually cruel?

In the end, it’s the words that add weight. Because how quickly and efficiently they demarcate who can do what, all the way from the Broadcasting Club to Temple Trees. This isn’t about the President, but he only had to pick up the phone that Friday evening for all his kind to become branded once again.

–

We talk about democracy a lot these days. But maybe our claims of democracy shouldn’t move on simple markers of identity. Those words which assume things of people based on who they are or seem to be and then prescribe entire realities onto them shouldn’t play a role in mobilising for democracy. This is how politics has always worked here, certainly, but bringing up these crude distinctions of identity have always served one set of people more than others: it has been neither the samanalun or the godayas, but the ones laughing their heads off at the front. And yes, this all sounds vapidly nice in the abstract, and harder to put into practice, but not excluding entire swathes of people from your idea of democracy right from the start is perhaps not too much to ask.

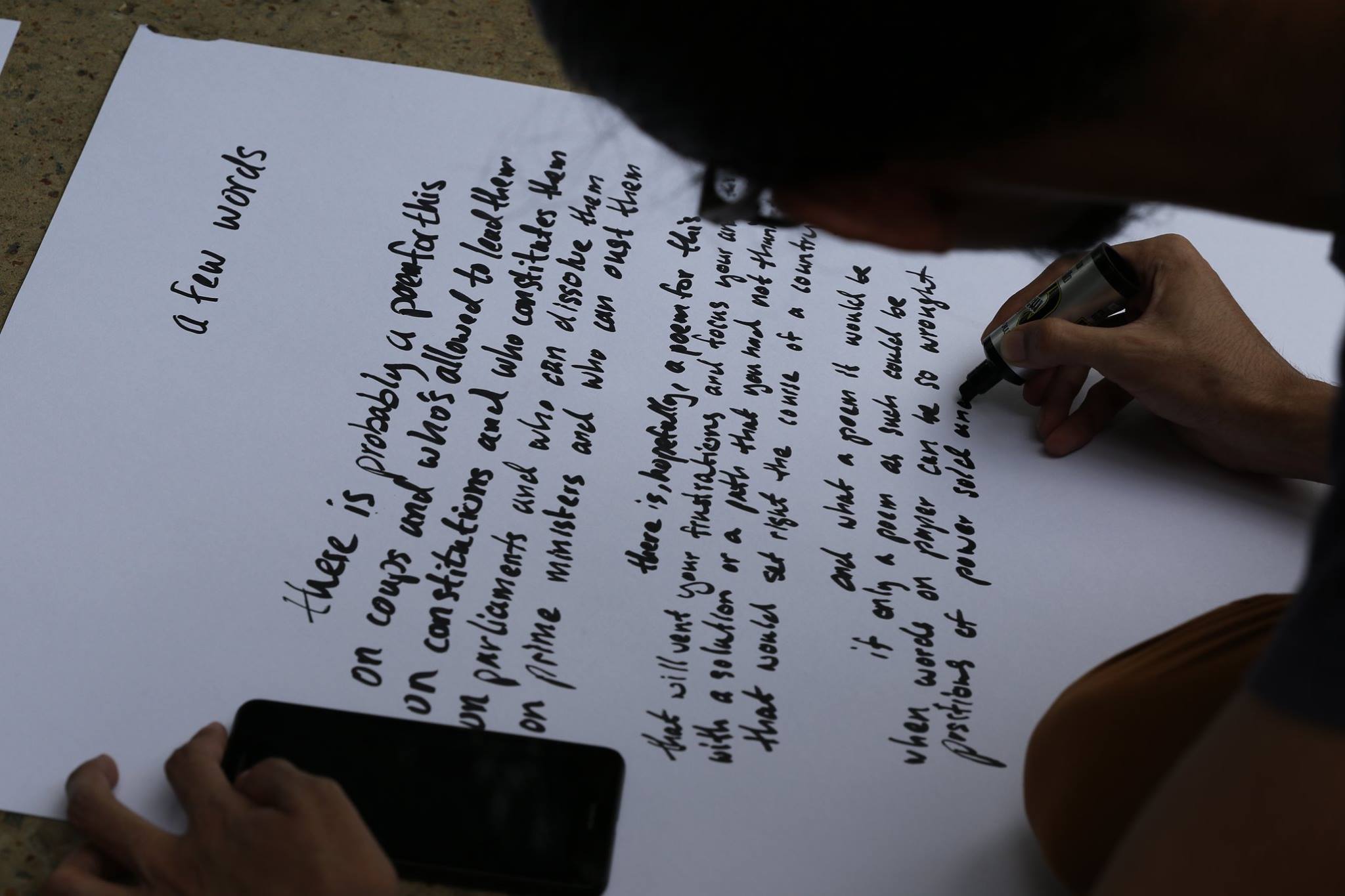

We are, once again, wondering how to pick up the pieces of our broken, twisted country, when strangers seem stranger than before. Perhaps our words can be a start.

Editor’s Note: Read more content on the coup here.