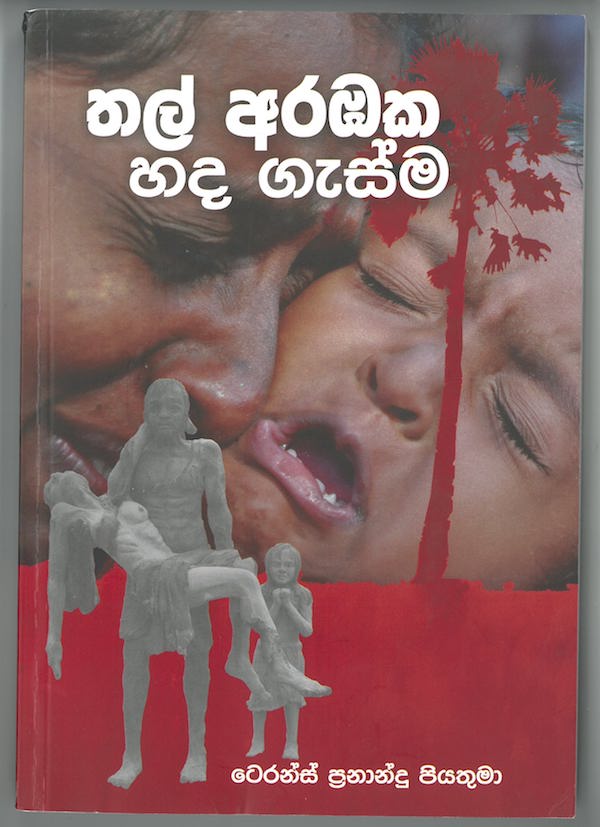

Heartbeat Of A Palmyra Grove

The background to anti-Tamil violence is the (Sinhalese) JVP uprisings against the government, the second of which was put down (according to Ajit Hadley Perera in an introductory note) with the loss of about 60,000 lives (page 246). The medical student Thrimawithane “was brutally killed by nailing on the head and [being] dragged on the roads by a jeep” (Perera, page 245). The beauty queen Premawathie Manamperi was forced to walk the street naked, tortured, raped and buried while still alive. Tortured bodies on burning tyres, and bodies floating on the river were not rare sights. Ben Bavinck writes in his Of Tamils and Tigers (Vijitha Yapa Publications, 2011) that outside an army camp in Baddegama, “a corpse has been hung in a crucified position with a large nail in its head”. A number of youth were beheaded in Kandy and their heads displayed with a sign reading, “Coconuts for sale”: see, Sarvan, Public Writings on Sri Lanka, Volume 2, pages 162 & 163. Reading Bavinck’s comment that children play the game of who has seen more dead bodies, reminds me of lines in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar (Act 3, Scene 1) which I paraphrase: Domestic fury and fierce civil strife; blood and destruction shall be common, and pity choked so that mothers will but smile when they see their children carrying weapons. Bavinck’s book was originally a diary, and he asks himself: What has gone wrong? How it is possible that these things happen in a country where Buddhism, a religion of peace and non-violence, is supposed to dominate life? (See, Sarvan, op.cit, page 163.)

Rev Fernando spoke out against abduction, torture and killings; he went in search of the missing young men and women, at great personal risk; helped to bury burnt bodies “killed by the army or para-military groups”. The same high ideals, courage and the readiness to pay the personal price will, I fear, now lead some to see him as deluded or, worse, a traitor: he observes that the soldiers who abducted, tortured and killed the sons and daughters of the people of the South are now hailed as heroes when they behave in the same way in the North and East (page 256). His comment that the JVP uprising was suppressed brutally, “without addressing the causes of the unrest” (page 265; italics not in the original) is relevant in another context. What’s more, some members of the JVP who “fought against discrimination seeking justice, today have become the partners of the oppressors and the oppressive system” (page 265). It was seen as brave, selfless and admirable of Rev. Fernando to fight against violence unleashed on Sinhalese during the JVP uprising, but for the same person to protest injustice and violence against Tamils is deemed traitorous. But here I am being unjust to Rev. Fernando because rare individuals like him neither see nor think on group-lines. For such, what matters is not being Sinhalese or Tamil; Buddhist, Christian or Hindu but belonging to our common humanity. They do not see themselves as trying to help Sinhalese or Tamils but only their fellow human beings. In the Christian tradition, man was made by God in His image. (Buddhism includes not only human beings but all living things in care and compassion. This accounts for vegetarianism, led by Buddhist monks, being widespread in Sri Lanka.)