Trump-Kim summit: Rollercoaster diplomacy vs. inclusive diplomacy

2018-06-01

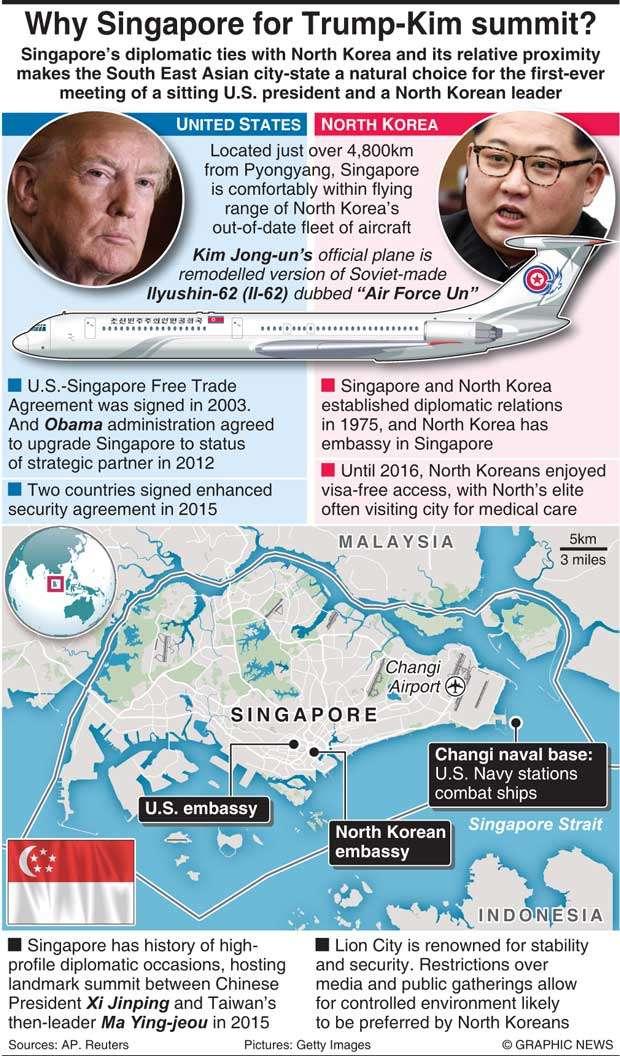

Till it happens, it is a tough call. Given the unpredictability that has now come to characterise the policies of the United States President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, the much-hyped summit is mired in uncertainty till the two leaders meet in Singapore on June 12.

Till it happens, it is a tough call. Given the unpredictability that has now come to characterise the policies of the United States President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, the much-hyped summit is mired in uncertainty till the two leaders meet in Singapore on June 12. First there was rhetoric or name calling. Trump threatened to unleash “fire and fury” on North Korea after the reclusive regime in August last year successfully tested Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles capable of hitting the US territory of Alaska. North Korea hit back, calling Trump mentally deranged. A month later, Trump ridiculed Kim as “Little Rocket Man” and threatened to “totally destroy” North Korea if it attacked the US or any of its allies. An angry North Korea responded with a bigger ICBM test, bringing the whole of the US under its range.

First there was rhetoric or name calling. Trump threatened to unleash “fire and fury” on North Korea after the reclusive regime in August last year successfully tested Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles capable of hitting the US territory of Alaska. North Korea hit back, calling Trump mentally deranged. A month later, Trump ridiculed Kim as “Little Rocket Man” and threatened to “totally destroy” North Korea if it attacked the US or any of its allies. An angry North Korea responded with a bigger ICBM test, bringing the whole of the US under its range.

In the face of North Korea’s nuclear missile muscle flexing, the Trump administration pushed for tougher United Nations sanctions on North Korea, with even China, North Korea’s closest ally, being forced to endorse them. As the hostilities were seen to be on the rise, the then US secretary of state Rex Tillerson announced the Trump administration was in direct contact with North Korea. In the meantime, South Korea’s behind-the-scenes peace offensive led by President Moon Jae-in began to work, with North agreeing to send athletes and a high-level delegation led by Kim’s sister, Kim Yo-jong, to the Winter Olympics in February this year.

Then, in April this year, what President Moon described as a “miracle” happened, when the leaders of the two Koreas met on the South Korean side of the truce village of Panmunjom, with the North Korean leader favouring the denuclearisation of the Korean peninsula. Against the backdrop of this historic summit, President Trump announced a possible meeting between him and the North Korean leader in what was seen as one of the biggest diplomatic shocks in the post-World War II history. The announcement came against the backdrop of a secret meeting between Mike Pompeo, the then CIA director and now the Secretary of State, and Kim Jong-un.

But after fixing June 12 as the date for the Kim-Trump summit and Singapore as the venue, the Trump administration on May 24, in a show of crude diplomacy, announced the cancellation of the meeting after North Korea reacted angrily to remarks made by Vice President Mike Pence and Trump’s hawkish National Security Advisor John Bolton. They had given the impression to North Korea that the fate that befell Libya and its leader Muammar Gaddafi would befall North Korea and

Kim Jong-un.

Kim Jong-un.

Taking the moral high ground, North Korea held a public ceremony to destroy its controversial nuclear site the same day Trump announced the cancellation of the summit.

On Friday, Trump made a dramatic about-face, announcing that the US-North Korea summit would go ahead as scheduled. Re-enter President Moon. Amidst such chaotic public utterings of Trump, in a refined act of delicate diplomacy, the South Korean leader met his North Korean counterpart on May 26 on the North Korean side of the truce village of Panmunjom in an effort to salvage the Korean peninsula’s historic opportunity for peace, reunification of the two Koreas and to end the Cold War era tensions.

As the roller coaster diplomacy, symbolising the capricious nature of the policies of Trump and Kim, kept the world guessing, heightened activity in Washington, Beijing and the capitals of the two Koreas point at a greater possibility of the Singapore summit taking place. Yesterday, US Secretary of State Pompeo met Kim Yong Chol, considered the right hand man of Kim Jong-un, in Washington, to discuss summit-related matters, while Russia dispatched its foreign minister Sergei Lavrov to Pyongyang for talks.

One cannot downplay the role of China in the turn of events. Kim Jong-un has in recent months visited China twice for crucial talks with President Xi Jinping, China’s virtual lifetime leader. It is expected that Kim Jong-un may visit China again ahead of the June 12 summit with Trump, and these meetings indicate that the Kim-Trump summit outcome will not undermine China’s national interest. US media have accused Beijing of coaching North Korea and blamed Beijing for giving Kim Jong-un the courage to take Trump head on. True, in terms of power, the US is much bigger than North Korea. In the event of a war, notwithstanding Kim Jong-un’s nuclear weapons and ICBMs, the United States could wipe out North Korea in a matter of days or weeks, if we were to assume that China would not intervene and South Korea, fearing a million deaths in the first hour itself of such a conflict, would not dissuade the US against such a war. Thus, for Kim Jong-un, ties with Beijing give him the necessary boost to meet Trump on an equal footing.

US media reports say there is as yet no agreement between the two sides on the terms of the summit. At the core of the summit is, however, the issue of the denuclearisation of North Korea. But the US side still does not know whether Kim Jong-un has made a decision to denuclearise.

If North Korea were to wind up its nuclear weapons programme, what will North Korea gain in return from the US? This could be the key question at the summit. Lifting the economic sanctions and promises of economic aid alone may not be enough. North Korea, probably goaded by China, may insist on the withdrawal of the US military from South Korea and other bases in Asia. Not only North Korea, but China and Russia also see the US deployment of Thaad missiles in South Korea as a major military threat and a hostile act.

If there is to be a positive outcome, ironically, it lies in a tested model -- the Iran nuclear agreement which Trump has discarded. Under this agreement signed by Iran and six world powers, including the US, Iran’s enriched uranium stockpiles were transferred to Russia. In North Korea’s case, China could be the guarantor of North Korean nuclear assets.

The meeting, if it takes place, therefore, will take place in an atmosphere of mutual distrust. If the Singapore dialogue were to bring results, it is imperative that China, Russia and Japan also come to the negotiating table.