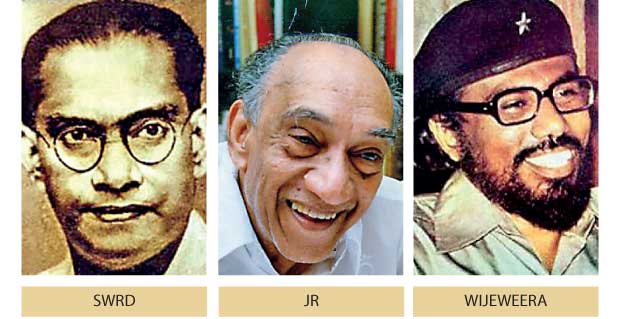

The three puppeteers

SWRD, JRJ and Wijeweera: three leaders who fundamentally changed Sri Lanka

“Example is not the main thing in influencing others. It is the only thing.”

~Albert Schweitzer

2017-11-22

2017-11-22The influence of Solomon West Ridgeway Dias Bandaranaike (SWRD), Junius Richard Jayewardene (JR) and Rohana Wijeweera (Wijeweera) on the local political theatre is unmatchable.

The great puppeteers of local political minds, they excelled in their chosen field and when they entered the arena, the aura that emanated from their physical statures, albeit SWRD and Wijeweera being slight and unimpressive, while JR was all persona and impeccable, the collective impression on the psyche of Sri Lanka’s politics and the altered course it instilled in the course of the country’s history, is undeniable.

In their presence, other political personalities withered; whether the effect is one of the positive results or negative consequence of a policy gone bad, the lasting quality of their policies, the assuredness of their unmitigated commitment to the cause they chose to serve made them stand apart from the rest amongst whom were some other brilliant personalities who strove so hard yet did not achieve the lasting and enduring results of political giants.

SWRD, JR and Wijeweera stood apart like three Generals, who had relegated the commanding presence of the likes of N. M. Perera, Colvin R. de Silva, Pieter Keuneman, Dudley Senanayake, R. Premadasa, Lalith Athulathmudali, Gamini Dissanayake, Sirimavo Bandaranaike, S. J. V. Chelvanayagam and Velupillai Prabhakaran to a not-so-great category.

Visionaries of a unique genre, the three giants stamped their impression for posterity not only for its own sake but for the country to follow and not so at the same time.

At this juncture of this column, let the reader be warned, especially in the context of Sri Lanka’s Post-Independence politics, how dare would Prabhakaran and Chelvanayagam enter the same arena, which had been sanctified by the Sinhalese Buddhist

‘Good Guys’?.

One may or may not agree with the policies, tactics and strategies of Chelvanayagam and Prabhakaran. But the influence they exercised over their own people was beyond dispute.

A thirty-year war could not have been sustained, had they been less influential and less consequential. But however much these second category of politicians gained a foothold on the Sri Lanka’s path to modernisation and economic salvation, none could do so with such lasting measure as it was demonstrated by SWRD, JR and Wijeweera, individually as well as collectively.

SWRD at the time he realised that there was no path for him within the ranks of the United National Party and its leader D. S. Senanayake, he made one of the most fundamentally sound decisions to leave it and go on his own.

Not only did he opt to break with the UNP and its heavy baggage of colonial subservience, he cleared a very savvy way for a novel brand of ‘identity politics’ of the time.

Not only did he opt to break with the UNP and its heavy baggage of colonial subservience, he cleared a very savvy way for a novel brand of ‘identity politics’ of the time.Political tribalism was in fact introduced by SWRD in 1956. His Swabhasha slogan, given leadership to by the Maha Sangha of the likes of Mapitigama Buddharakkhitha, Chief of the Kelaniya Vihara and eventual conspirator of his assassination, set apart the Sinhalese Buddhists from the rest of the country.

This was a fundamentally significant landmark in the country’s course of socio-political life.

Setting the common man apart from the rest, setting him as a victim of years-long suppression and negligence, rendering him a distinct personality and identifying him in terms of socio-economic values and then unleashing his thereto suppressed desires, class-enmities and parochial beliefs, if not checked at necessary intervals and junctions, could be devastating and destructive.

Let the reader be warned, especially in the context of Sri Lanka’s Post-Independence politics, how dare would Prabhakaran and Chelvanayagam enter the same arena, which had been sanctified by the Sinhalese Buddhist ‘Good Guys’?.

SWRD was a man who was assassinated by the very forces he willingly released. In mere three years, the heroic entry of the common man’s era became somewhat an unwelcome torrential rain of misplaced and misjudged values and measures.

Political power assuming all-powerful dimensions and becoming a dangerous tool in the hands of an uneducated and checkered individual had had consequential effects and cascading of these tendencies down generations have today produced a totally corrupt culture.

In the context of a nation’s march to progress and growth, provision of a ‘place in the sun’ for the common man is a highly creditworthy ideal and those who pursue such an ideal should be encouraged. Yet when such a pursuit is glaring at the defilement of values and measures that set Sri Lankan culture as one rich and wealthy in religious and ethnic harmony, the story becomes completely disfigured and warped. The common man has become his own enemy. The lofty ideals he had set for himself have been subordinated to avarice and pursuit of mundane pleasures.

While the common man’s social standing has risen way above his expectations, the Swabhasha policies of the Government of SWRD set the country’s most precious asset, youth, two or three generations behind his contemporaries in the Asian region. The 1956 revolution became a transformation of a nation from bad to worse instead of good to better.

JR, on the other hand, had a very difficult hand to deal with. On merit alone, J R should have become the country’s leader after the demise of D S Senanayake. Yet he had to wait another twenty-five years to ascend to the throne. From 1952 to 1977, the road that led JR to the pinnacle of power was visited with more cacti than roses.

Yet when he arrived there, in Benjamin Disraeli’s immortal words: “after having climbed to the top of the greasy pole”, JR, in the words of his own biographer, K M de Silva, was an old man in a hurry.

Disenfranchisement of Sirimavo Bandaranaike, though at the time of its execution looked draconian and self-serving, was the logical outcome of a legitimate findings of a Special Presidential Commission established for the purpose of finding the truths about gross abuse of political powers so exercised by the two Bandaranaikes, Sirimavo and Felix Dias.

Yet, JR’s greatest contribution to the country’s progress was the opening of the economy which was manacled by the shortsighted socialist policies of the Sirimavo Bandaranaike-led left-of-center Government of 1970 – 1977.

As much as SWRD’s Swabhasha policies turned the national consciousness of Sri Lanka, JR’s economic policies fundamentally changed its economic character. It’s never to return to the outdated left-wing socialism that was the fashion of the third-world countries of the fifties and sixties.

The socio-political currents unleashed by SWRD and JR respectively had plusses as well as minuses. It’s too early to judge their ultimate effect on the history of the country at large. As leaders of a developing nation, both SWRD and JR made a conscious effort to serve the country they called their motherland and there is no evidence whatsoever of malicious intent on their part.

Their commitment to the cause they chose to serve was total; their efforts untiring and while SWRD was lackadaisical in his execution, JR exhibited ruthless efficiency.

When JR got down to work, one could not have found a more disciplined leader.

Now we come to the third leader who contributed to a fundamental change in Sri Lanka’s political psyche- Rohana Wijeweera. Born on Bastille Day, July 14, 1943, Rohana Wijeweera hailed from a coastal fishing village situated in southern Sri Lanka and belonged to the Karava Caste hierarchy.

By way of five oversimplified classes, Wijeweera transformed the minds of the rural youth into Angry Young Men and Women bent on revolutionising the county’s political path for good.

Violent overthrow of a democratically elected Government did not occupy the mind of the average youth in Sri Lanka. Wijeweera simply managed to alter that dynamic and his pioneering efforts in the formative years of his creation, Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) are legendary.

Long before Prabhakaran initiated his own Tamil militancy in the North, Wijeweera showed in no scarce terms that the mind of youth is very much prone to the vagaries of violent and exhibitionistic propensities. Within a matter of twenty-three years, from 1966 to 1989, Wijeweera launched two violent uprisings, killing hundreds of political opponents and instilling dread and fear into the minds of a docile community, whose most violent reaction to Government suppression up to that time was a failed Hartal and countless general strikes at workplaces.

An archetypical speaker in the vernacular, Wijeweera had no match in mob oratory; the flow of the language mesmerised thousands of activists and they literally sacrificed their lives for this man whose untiring dedication to the cause of the suppressed masses was never a subject of debate.

Wijeweera stirred the conscience of Sri Lanka’s youth. A sense of romanticism entered the realm of the nation’s politics and that romanticism captured not only the youth, it left an indelible legacy among the middle-aged, lower-middle-class men and women. His oratorical skills were equalled by none.

He pioneered a movement that led the country’s youth in a violent revolutionary fervor. His contribution to modern Sri Lanka’s history is undoubtedly unique and fundamental.

Of the three leaders we discussed here, two, SWRD and Wijeweera, were educated abroad; SWRD at Oxford and Wijeweera at the Patrice Lumumba University, Soviet Union. JR was a total local product, Royal College, University of Ceylon and Law College.

The two who were educated abroad advocated Left-wing political theories while the local-educated JR, promulgated Capitalism.

SWRD and Wijeweera were assassinated, one by a Buddhist Monk and the other by the Security Forces of the country. JR died in bed, at the ripe-old age of 90.

The writer can be contacted at vishwamithra1984@gmail.com