Do rent controls work?

By Martin Williams-29 SEP 2017

By Martin Williams-29 SEP 2017In his speech at the Labour Party Conference this week, Jeremy Corbyn promised to introduce rent controls.

The announcement delighted many struggling private renters, but critics responded saying the move would damage the housing sector and be a “disaster for tenants”.

So who’s right?

What does ‘rent control’ actually mean?

The main problem with the rent controls debate is that it is unclear what exactly we’re talking about. There are a number of different ways of “controlling rent” – and different policies could produce very different results.Broadly, they can be divided into three categories:

- Capping rent

- Capping increases to rent

- Temporarily freezing rent

Likewise, the second option – capping rent increases – could be accompanied by rules to set a minimum length on tenancy agreements. This would avoid a situation where landlords frequently raise prices in between short tenancies.

At the moment, it is not clear what Labour is proposing. The party’s election manifesto pledged to introduce “controls on

rent rises”, but did not mention an overall cap on initial rent prices. It said: “Labour will make new three-year tenancies the norm, with an inflation cap on rent rises.”

However, in his conference speech this week, Mr Corbyn seemed to talk in broader terms, promising to “control rents”. He said: “Rent controls exist in many cities across the world and I want our cities to have those powers too.”

Was this a change in policy, or just a change in rhetoric? Even if it is a policy change – committing to fix overall rent – it is not clear where the prices would be set.

Without knowing what policy is being proposed, it’s impossible to assess what the impact will be.

What happened with rent controls in the past?

Rent controls were in place for most of the 20th Century in the UK, having first been introduced in 1915 to deal with spiraling rent prices. Both rent and mortgage interest payments were fixed. Rules were also brought in to make it harder for landlords to evict tenants and re-occupy the property.By 1918, landlords joined tenants in calling for an extension of these controls (because of their below-inflation interest rates on mortgages).

These regulations were relaxed gradually over the next couple of decades, but in 1939 the government re-introduced full control on rent – which stayed in place until 1968.

This period coincided with a major housing shortage after the Second World War. For tenants, this meant rent controls were more important than ever, to avoid market-rate price hikes. But there was also a rapid decline in the housing sector. A parliamentary report on rent controls explains:

“Rent yields were hit hard and landlords took opportunities to sell up and invest elsewhere.”

Some have blamed this on rent controls, while others look at problems with the private sector. But the reality is likely to be far from black and white. The parliamentary report says: “The decline of the sector after 1945 has been attributed to a ‘complex set of factors’ of which rent control is one.”

The very particular circumstances of Britain’s past experience of rent controls make it tricky to draw direct comparisons with what the policy might look like today. If one lesson can be learnt, it is probably simply that rent controls do not operate independently of other economic factors.

What type of rent controls work best?

The criticism of rent controls centres around the potential impact it could have on the housing market. Some say that restricting landlords’ income will lead many to sell their properties and not invest in new developments.Of course, if rent controls were matched with new council houses and state-subsidised developments, then it could be argued that reductions to the private sector do not matter so much. Indeed, in its manifesto, Labour promised to build “at least 100,000 council and housing association homes a year for genuinely affordable rent or sale”.

That said, the private rented sector currently accounts for some 4.5m households in the UK, so rent controls could have an extremely deep impact – depending on how they are implemented.

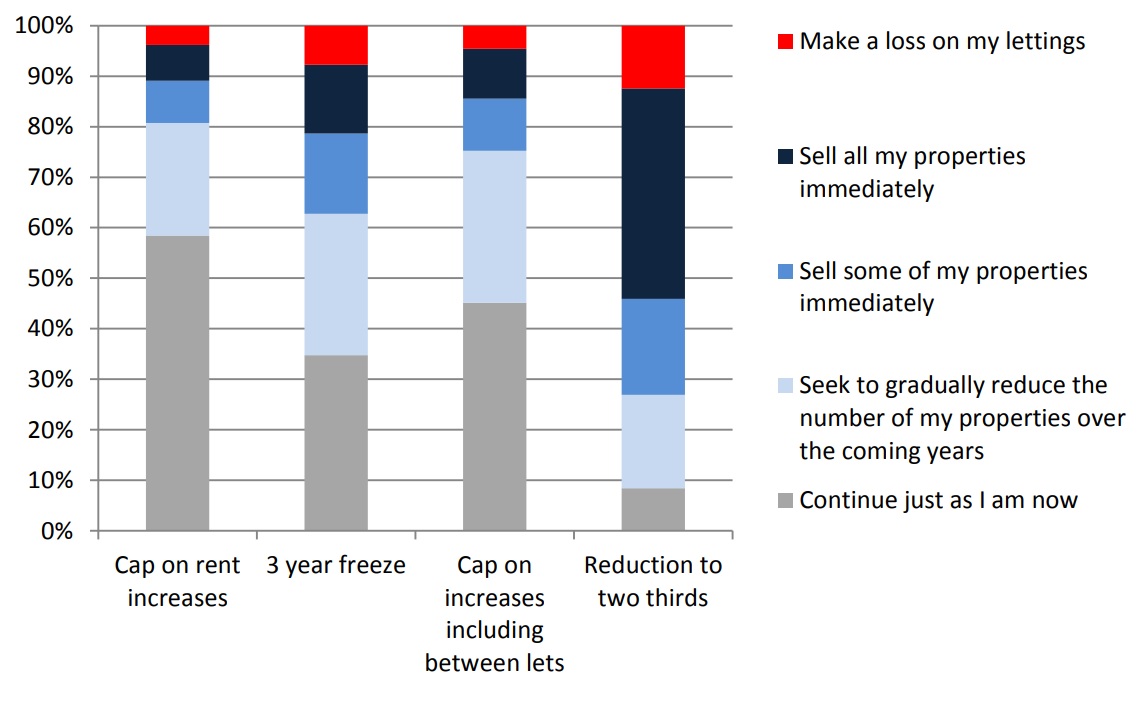

A report in 2015, from Cambridge University, did a survey of private landlords to ask how they would respond to various types of control. The results need to be viewed with caution because the researchers pointed out: “The relationship between what people say they would do, and what they actually would do, given a specific situation, is inevitably uncertain. This is particularly so for a politicised issue such as rent controls where there are strong feelings involved.”

Here’s what their survey said:

With most of the rent control scenarios they looked at, the researchers said there would be “small reductions in average rents”. This would lead to an “aggregate loss of rental income to the sector of between 0 and 5.5 percent”.

With most of the rent control scenarios they looked at, the researchers said there would be “small reductions in average rents”. This would lead to an “aggregate loss of rental income to the sector of between 0 and 5.5 percent”.“This is a relatively small loss of income and not, in itself likely to cause a substantial change to the size of the sector,” it said.

The only scenario which would see a significant income reduction to the housing sector is when initial rents are initially set well below market rates. It is estimated that this could knock 37 per cent of rental revenue in England by 2025.

But for all the other scenarios the report examines, revenues would decrease by no more than 1.7 per cent.

Dramatically forcing rent reductions could lead to an exodus from the

housing market, the report warns. “This is likely to cause a housing market shock and possibly a significant fall in house prices at least

until the market corrects itself.”

This would probably have a negative affect on low-income renters. The homeless charity Shelter has warned it could “force a significant number of landlords to sell their home, as they could make more money that way”.

“This is where the risk comes in for low earners. They can’t afford to buy and increasingly rely on the private rented sector. As landlords sell up, they would be left with fewer places to live.

“In the absence of a much larger supply of council and social housing, that risks pushing people into homelessness.”

The verdict

Rent controls could mean any number of different policies. They can have vastly different effects, and they also need to be considered in the context of the wider economy and housing policy.It seems perfectly possible that many forms of rent control would not significantly damage the housing sector. Government support for new developments could help fill the gap of any reductions to private sector.

But, equally, it is possible that more extreme forms of control could have a deep and negative impact. That is not to say that they could never work, though – especially if accompanied by other factors like financial incentives for landlords or a large increase in council housing.