Behind the protest - Families of the disappeared: Ratheeswaran

30 Jul 2017

For months relatives of the forcibly disappeared have been protesting on the streets across the North-East, demanding to know the whereabouts of their loved ones. Despite years, sometimes decades, of various government mechanisms and pledges, their search for answers continues.

In this series of interviews conducted since May 2017, Tamil Guardian goes behind the protest to the individual stories that make up this unyielding movement of Tamil families of the disappeared.

Ratheeswaran

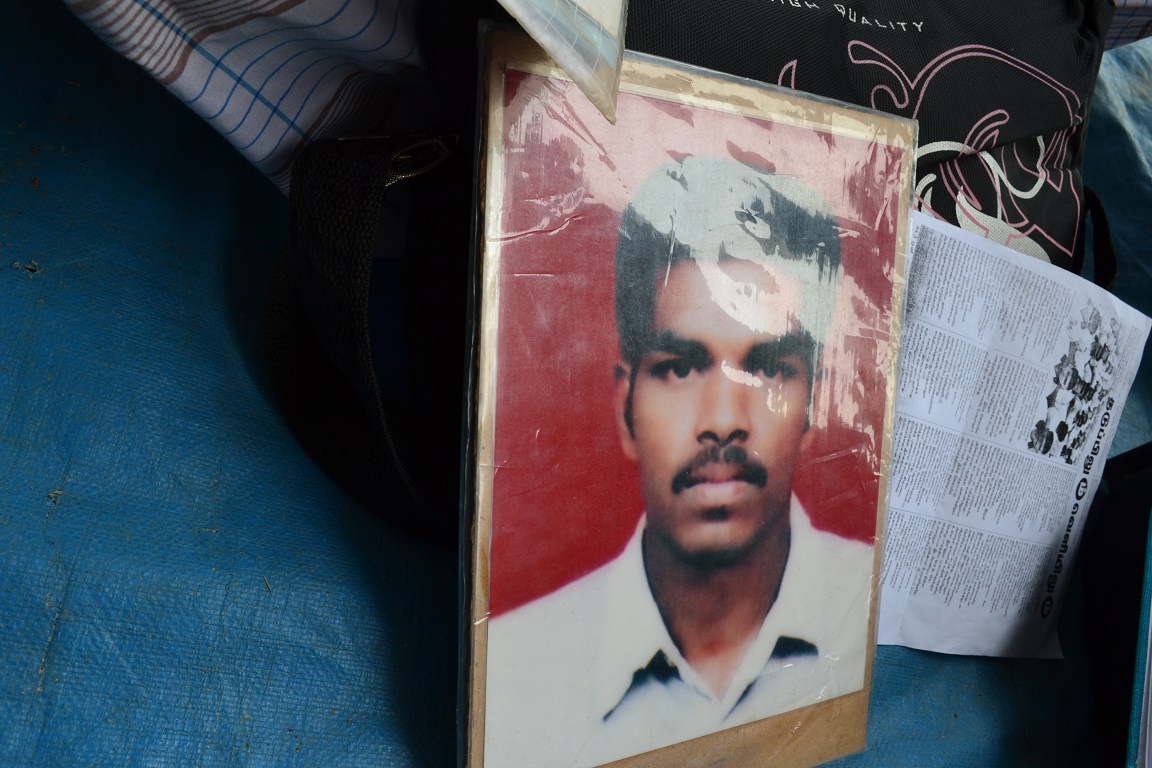

Ratheeswaran was 27 years old when he was disappeared, last seen with the Sri Lankan military in June 2008.

“He was injured and the army took him,” says his father, who sits outside the Kandasamy temple in Kilinochchi alongside dozens of others searching for their loved ones. They’ve been protesting for over 150 days, demanding answers to the whereabouts of their disappeared family members.

In mid-2008, the Sri Lankan government was in the midst of a massive military offensive and was rapidly advancing into LTTE territory. Ratheeswaran, the youngest boy in his family, was working in a garage before he was forcibly recruited to the LTTE his father says. Thousands had been displaced and killed in the fighting at the time.

His father was told that his son had been injured in Manal Aru before he was taken by the military into Sri Lankan government held territory. From then onwards, his whereabouts were unknown.

“The army took him and there was an injury on his leg, so they carried him,” continues 66-year-old Muththan. “They didn’t tell us which hospital… at that time you couldn’t go to see them either. You couldn’t go past Vavuniya.”

|

Muththan still does not know which hospital Ratheeswaran was taken to and in the chaos of the final stages of the armed conflict, it proved impossible to locate him. Speaking to the Sri Lankan security forces was fruitless. In his search for his son though, he eventually had a breakthrough.

An acquaintance of the family who works as a jail guard in Colombo said Ratheeswaran was being held at the infamous Welikada Prison. “The jail guard is on good terms with us,” says Muththan. “He said his name and details were there and for my son in law to come right away.”

Nestled in the southern capital, Welikada Prison – also known as Magazine Prison after the British used the site to store ammunition – is a maximum security jailhouse and the largest on the island. As many as 4,000 prisoners are thought to be housed at the jail, including several Tamil political prisoners. The prison has gained notoriety for its frequent riots, in which Sinhala mobs have murdered Tamil inmates.

“My son in law went and he knows Sinhalese,” he recalls, which would allow him to navigate through the South. “But when he went they said that he is no longer there and that they have moved him.” Prison officials went on to decline any knowledge of him being kept at the site.

It was now 2009.

|

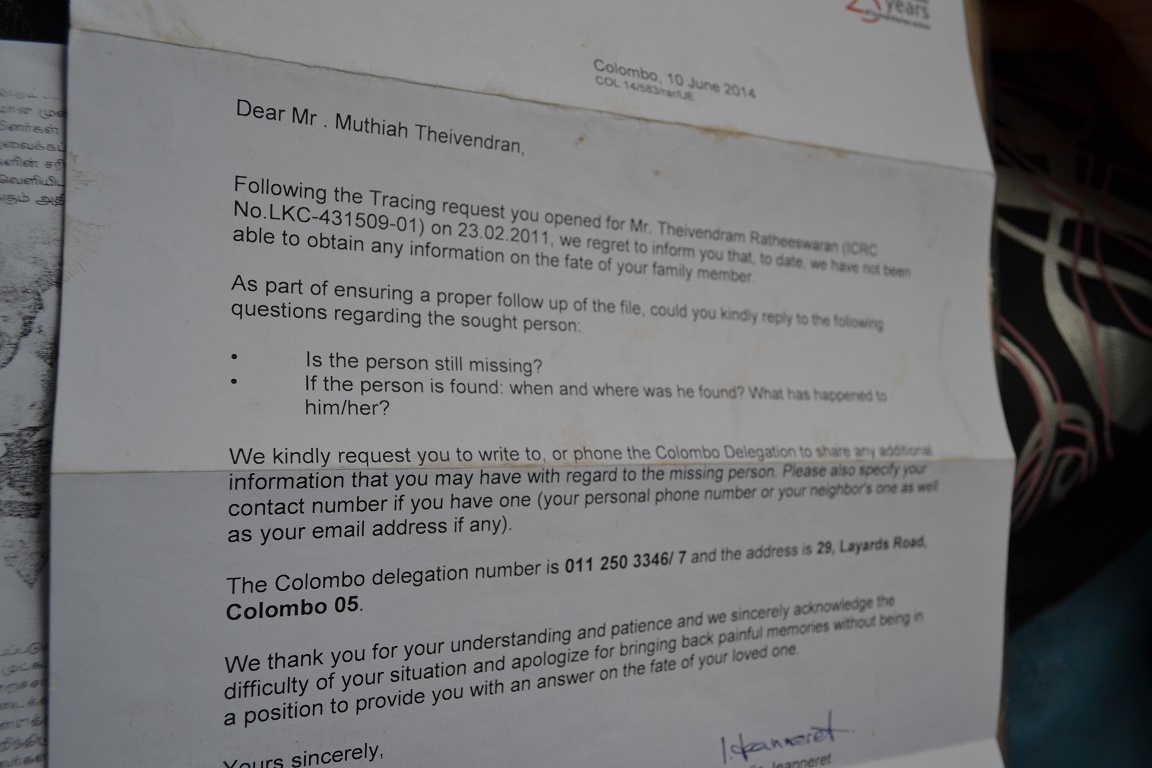

For the next few years, Muththan had no further information on the whereabouts of his son. Like the others with him, he did not give up hope of finding his child, even opening up a tracing request with the ICRC in 2011 in the hope that international organisations would be able to locate him.

It was several years later before he would hear any more information on Ratheeswaran. Another Tamil man who had been arrested by Sri Lankan authorities and put through the government’s ‘rehabilitation’ program got in touch with Muththan after being released. Thousands of Tamils were put through ‘rehabilitation’ camps scattered across the island, through which Colombo claims “misguided youth” would be “reintegrated” into society. In these camps, torture and sexual violence was reported to have been rampant.

“The 170 people they released after “rehabilitation” in the 3rd or 4th year… someone from there said that your son was with me,” says Muththan. “He was going to say where he was with my son but then he didn’t say because he was too scared to say more.”

“My son was with him.”

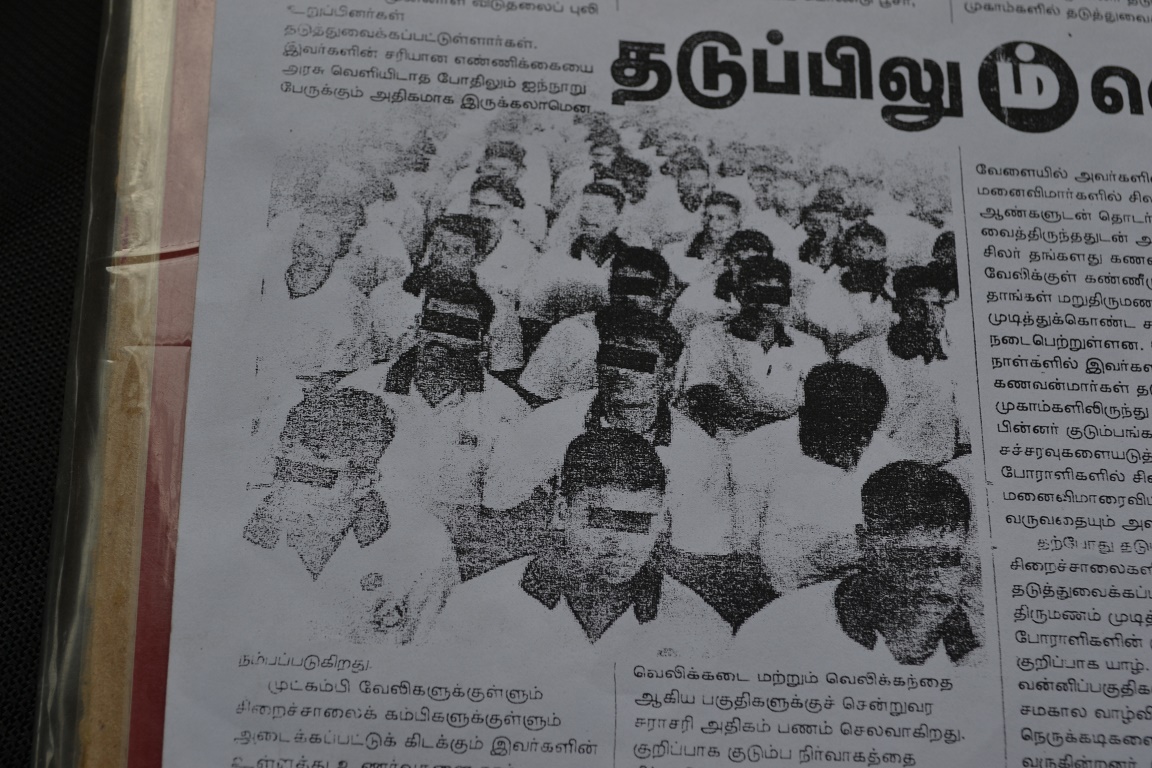

Muththan began scouring the media looking for any clues that could lead to Ratheeswaran being located. As he pored through newspapers and websites, he came across an article in the Sudar Oli dated 26th March 2012. In the corner of the page is a photo, showing rows of seated young Tamil men, all dressed in government issued polo T-shirts, their eyes censored over with large black rectangles.

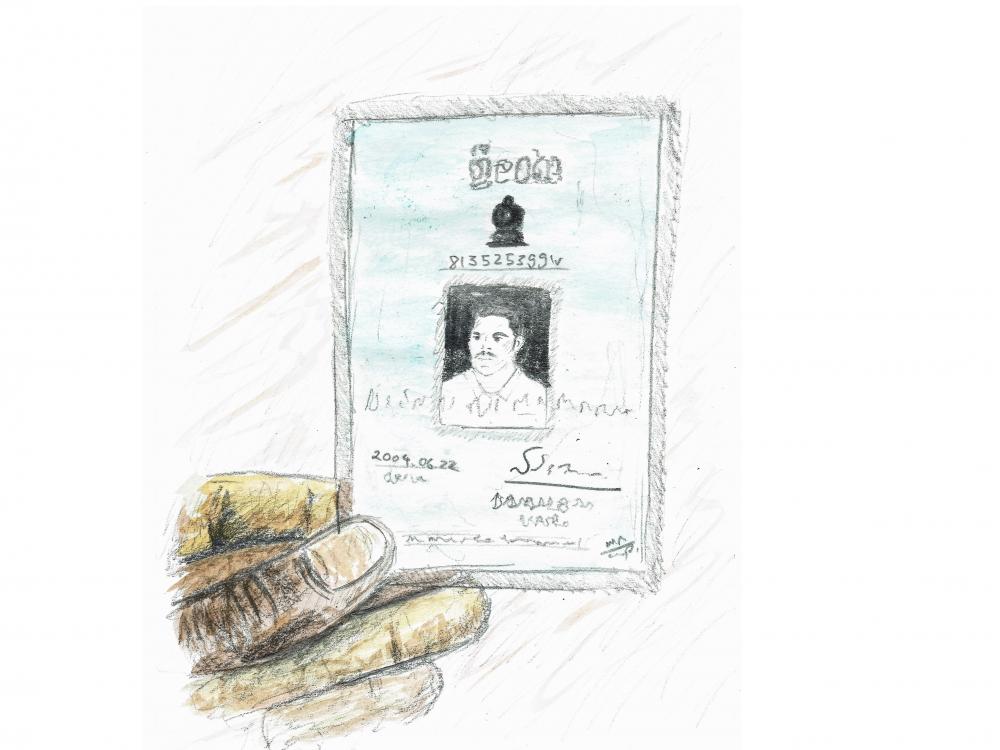

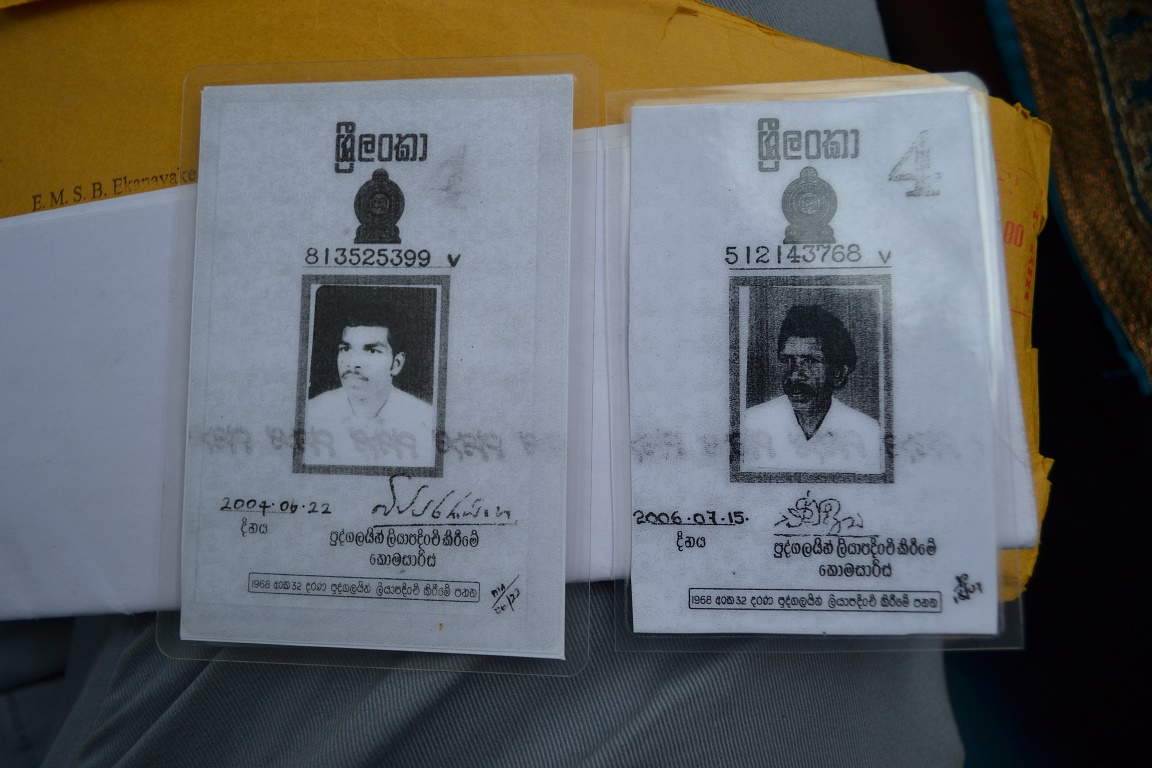

Sat on the second row is Ratheeswaran, says Muththan, sporting the same thick black moustache he has on his Sri Lankan identity card.

|

“Yes… look at this photo,” he says pointing to a photocopy of the article and Ratheeswaran’s identity card for comparison. “Look at it from the back,” he gestures, holding the page towards the light. “You can see it better.”

“Yes… look at this photo,” he says pointing to a photocopy of the article and Ratheeswaran’s identity card for comparison. “Look at it from the back,” he gestures, holding the page towards the light. “You can see it better.”

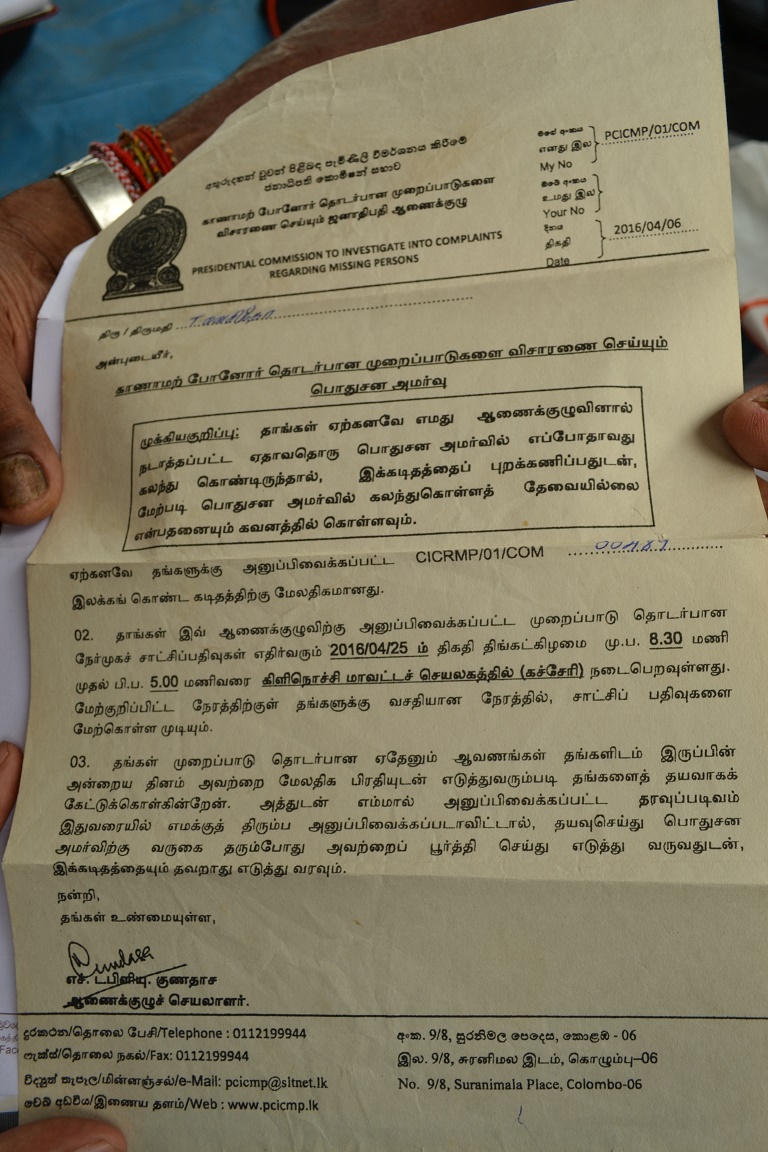

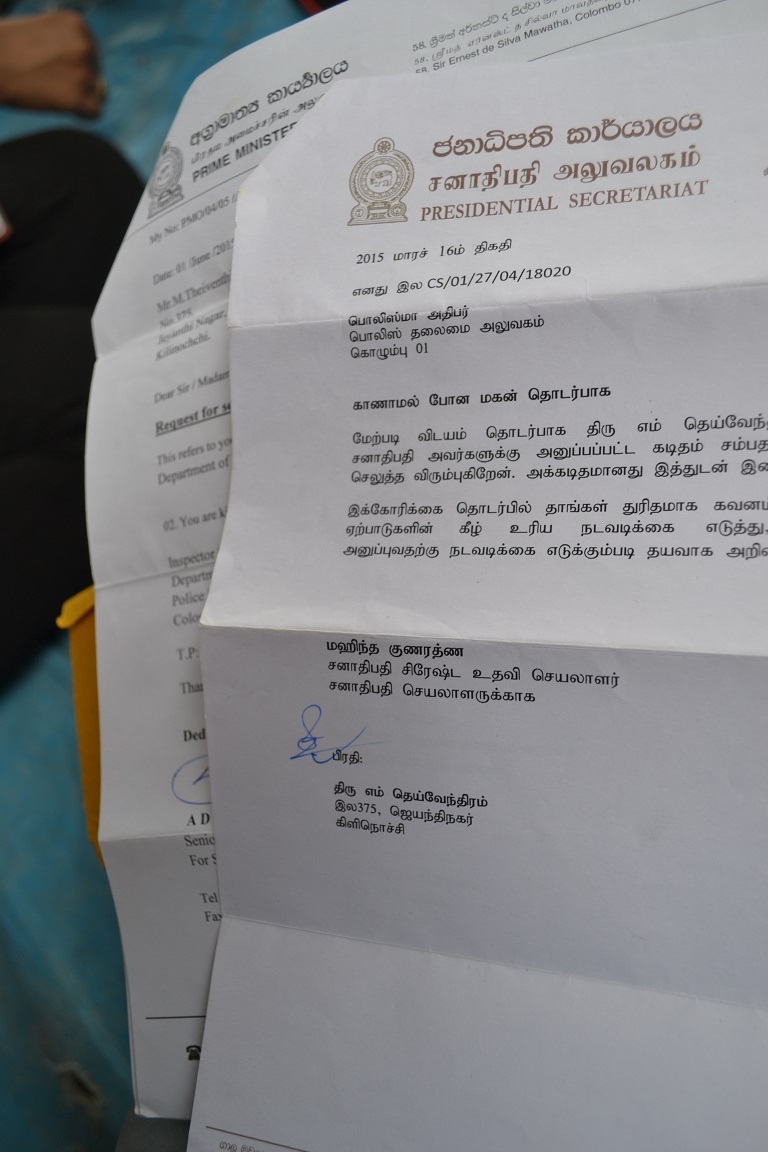

Muththan is convinced the Sri Lankan state is still holding his son. He pulls out reams of paperwork from his plastic bag that he carries with him. In it are documents, meticulously detailing the struggle he has gone through to locate his child.

He has appeared before the Presidential Commission for Missing Persons, and written directly to the Presidential Secretariat as well as the Prime Minister’s Office. He still has no answers.

|  |

In 2014, the ICRC wrote back to Muththan, informing him that “we have not been able to obtain any information on the fate of your family member”.

“Is the person still missing?” the ICRC asked. “If the person is found: What has happened to him/her?”

|

Muththan’s wife no longer comes to protests. “She is also sick,” he says. “Sick from thinking about our son.” They both still hold out hope he will be returned to them.

“My son is alive,” he cries. “Everyone is saying he’s alive.”

“I’m waiting for my son,” he pleads, clasping his hands together in prayer. “You can take me and bring back my son, I’m begging you. You don’t need to do anything else for me. Bring back my son and take me instead.”

“I beg you.”