The Story Of A Societal Purpose

By Mahesan Niranjan –April 23, 2017

We met after a gap of several weeks in the famous Bridgetown pub for our regular drink. My partner, the Sri Lankan Tamil fellow Sivapuranam Thevaram, has been travelling, visiting the Central Asian country of Kazakhstan, a place he has never been before. “My colleague and I were there, teaching an intense course machan (buddy), a whole semester worth of material packed in two weeks,” Thevaram said to me over our first round of Peroni. My friend is from the club of Artificial Intelligentsia, a necessary path of salvation for those who lack the real thing, as I often tease him.

Thevaram knew nothing of Kazakhstan before, other than the packaged media image of a large ex-Soviet Union country whose sole purpose was to serve as the launching pad for Russian satellites — just the same way the United Kingdom serves as the largest aircraft carrier of the United States of America. As he planned his journey, his colleagues at work wished upon him zero probability of getting kidnapped by horse-riding warriors who were direct descendants of the powerful Genghis Khan.

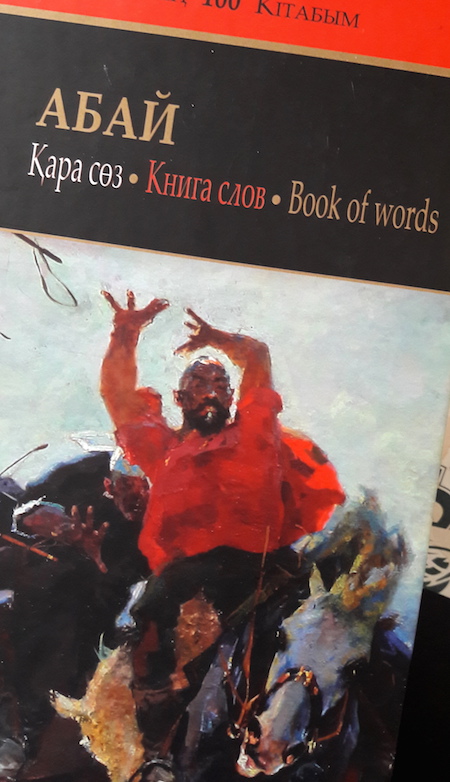

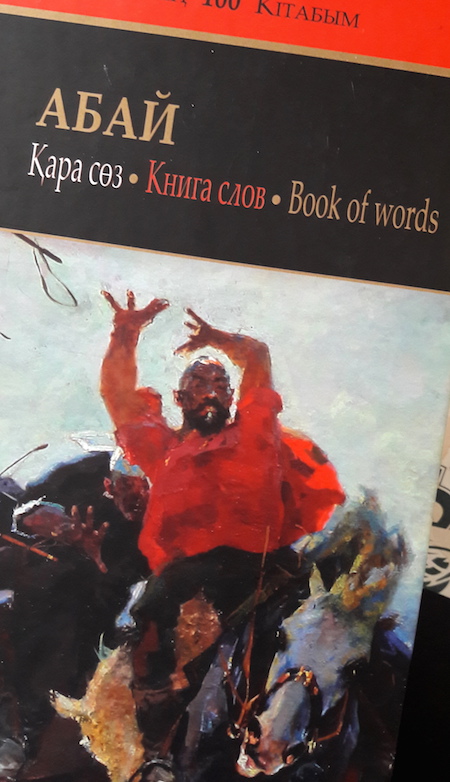

Amazing how rapidly such prior images shatter when you actually visit a place and mix with people there! Back in the Bridgetown pub Thevaram reported having had a lovely time packed with work, friendship, fun and food. In the flight back he read some work by Abai Quananbaiuli, a Kazakh philosopher and poet, acknowledged widely as a reformer and nationalist, from a book his class had presented him earlier that day. Now, Thevaram, having lived through the rise of Sinhala and Tamil nationalism in Sri Lanka, and observing how it manifested into a deadly war, culminating in the massacre of thousands thirty years later, usually has no time for nationalist sentiments. He dismisses them because they are usually built on fiction, glorifying some past about a two thousand year old civilization, or on who might have arrived on the island first.

Abai’s Words, however, had a very different flavour which appealed much to Thevaram. It had paragraph after paragraph of societal self-criticism and reflection: “Where lies the cause of the estrangement amongst the Kazakhs, of their hostility and ill will towards one another? Why are they insincere in their speech, so lazy, and possessed by a lust for power?”

And he writes during times of Russian occupation of his land: “One should learn to read and write Russian. It is the key to spiritual riches and knowledge, the arts and many other treasures. If we wish to avoid the vices of the Russians while adopting their achievements, we should learn their language and study their scholarship and science […]” Thevaram spent the whole seven hours of flight reading and admiring this fascinating approach.

Nationalism built on reflection than on manufactured myth! The message to study the language of the invading oppressor! Wow!!

“Now has anyone tried that in our context?” he asked himself, knowing full well the answer might be the label “traitor” in early days of our nationalism, and a body found in close proximity to a lamp post during more later stages.

Yet, no scholarly writing can match what you learn by visiting a place and carrying out your own observational social science research.

On the previous evening Thevaram and his colleague were treated to a fantastic dinner at a Georgian restaurant — a long evening of food and discussions which went on till mid night. They then had to go back to their hotel and one of their hosts – Kiliyoparada (not her real name), a young lady of exceptional beauty — accompanied them to make sure they don’t get lost.