Sri Lanka: Captivity & Diversity In Focus

By Mark Salter –December 31, 2016

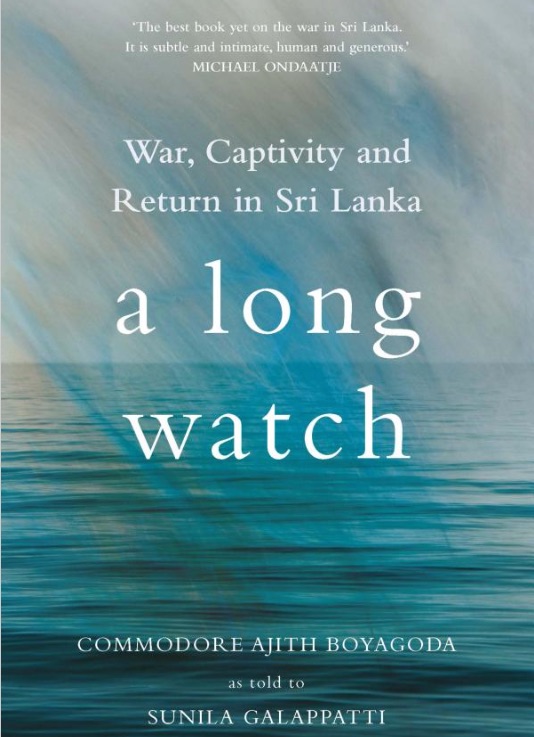

2016 has been a good year for books about Sri Lanka at Hurst, a noted UK-based publishers specialising in Asian – and in particular South Asian – affairs. First came A Long Watch: War, Captivity and Return in Sri Lanka by Commodore Ajith Boyagoda, as told to Sunila Galipatti, a writer and former Director of the Galle Literary Festival.

As befits a prisoner of war memoir A Long Watch is couched in direct, lucid prose. It tells an extraordinary story. In September 1994, at the height of the civil war, Boyagoda was commanding one of the Sri Lankan Navy’s largest warships, the Sagrewardene. South of Mannar it came under attack by LTTE vessels and eventually sunk. Unlike many of his crew Boyagoda survived the assault, only to be pulled out of the sea with the other survivors and hauled away by LTTE cadres.

The highest-ranking officer ever captured by the Tigers, Boyagoda spent the next eight years in captivity, eventually being released in 2002 as part of a prisoner exchange deal. The majority of the book covers his long years of imprisonment. The picture that emerges is a complex one. Boyagoda makes no bones about his rejection of conventional ‘evil terrorist’ characterizations of the Tigers. He is also at pains to emphasize how fairly he was treated by his jailors, expresses sympathy for the injustices visited on the Tamil population, and even shows empathy for his captors, many of whom were, as he notes, forcefully conscripted by the Tigers in their youth.

The highest-ranking officer ever captured by the Tigers, Boyagoda spent the next eight years in captivity, eventually being released in 2002 as part of a prisoner exchange deal. The majority of the book covers his long years of imprisonment. The picture that emerges is a complex one. Boyagoda makes no bones about his rejection of conventional ‘evil terrorist’ characterizations of the Tigers. He is also at pains to emphasize how fairly he was treated by his jailors, expresses sympathy for the injustices visited on the Tamil population, and even shows empathy for his captors, many of whom were, as he notes, forcefully conscripted by the Tigers in their youth.

As Galipatti has acknowledged elsewhere, telling a story as exceptional and as potentially charged as this one was never going to be an easy task. As a consequence she sticks firmly to a first-person narrative, keeping herself and her opinions firmly in the background. Inevitably, the resulting account has proved controversial. In particular, following its publication accusations that in a wartime version of the ‘Stockholm Syndrome’ Boyagoda had sold out – even spied for – the Tigers were voiced in a number of quarters.

Certainly, the return to the South in 2002 did not prove easy for Boyagoda: eventually released from the Navy, initially he struggled to relate to his children and family, from whose lives he had been separated for so long. Overall, the account of Boyagoda’s wartime captivity is best read for what it is: one man – albeit a particularly thoughtful, sensitive one’s – experiences, as opposed to what it is not: an objective, critical account of the Sri Lankan conflict.

Next came Madurika Rasaratnam’s Tamils and the Nation: India and Sri Lanka Compared. An altogether denser, more academic work of comparative political history, Rasaratnam’s book is a magisterial effort to address a central question. Why did India and Sri Lanka’s post-independence evolution of follow such hugely differing trajectories with respect to their Tamil populations? Why was it the case, for example, that whereas by the late 1960s, previously independence-oriented political parties such as the ADMK had fully embraced the notion of Tamil Nadu’s place within the wider Indian polity, in Sri Lanka the Sinhala-dominated state’s continuing failure to accommodate Tamil aspirations eventually succeeded in transforming political forces that had vocally advocated independence from Britain and national unity into advocates of Tamil Eelam – and eventually into those, such as the LTTE, with no qualms over the use of violence to achieve that goal?