Heritage & Nationalism: A Bane Of Sri Lanka

By Jude Fernando -March 30, 2015

“Those who control the past control the future. Those who control the present control the past” -George Orwell

“The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there”- L.P. Hartley.

The current practices of archeology and their complicity with rebranding of archaeological heritage as national heritage have contributed to the ethnic tensions, civil war, injustice, inequality, and violence in the Sri Lankan society. The pretense that archaeology is an apolitical profession is a form of complicity with these social ills. In many societies, archaeological knowledge was the historical basis for nation builders and their antagonists (e.g. separatists/sub nationalists), who reclaimed or plundered their antiquity, and reshaped it to support discriminatory social, economic and political practices. Sri Lanka is no exception.

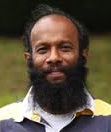

Formerly a Tamil village known as Kokachankulam located in Vavunia North has been renamed as Nandimitragama

Nation building and archeology are intimately related. According to Randall McGuire “nationalists muster archaeology both to prove their myths dispassionately and to reveal and reconstruct an “authentic” objectified heritage.” In most societies archeology evolves and becomes institutionalized within the political and cultural parameters set by the nation-building priorities set by the state. Under these circumstances archeology is politics by other means. Denying the political nature of archeology is a form of self-deception.

Good governance (Yaha Palanaya), as a political response to pernicious social and political consequences of nation building, will elude us unless we are prepared to radically change the current mindset about the relationship between country’s archaeological heritage and culturally distinct collective identities and landscape. People’s entitlement for freedom, equality and justice should be the driving force behind the reasons for our search for archeological knowledge and how we chose to act upon it. Archeology fails to make a positive contribution to the society while it is a prisoner of the ethnonationalist politics of the state. Under such circumstances archeology becomes complicit with political and cultural practices that use archeology not “necessarily always to better understand the past, but to use the past to legitimize the present.” The point here is not that the past “literally speaks to the present,” but rather, “when the past is used to legitimize the present, we insist that it is saying what we want to hear, even if the thoughts we are imputing to the past may have been alien to it.”[1] Read More