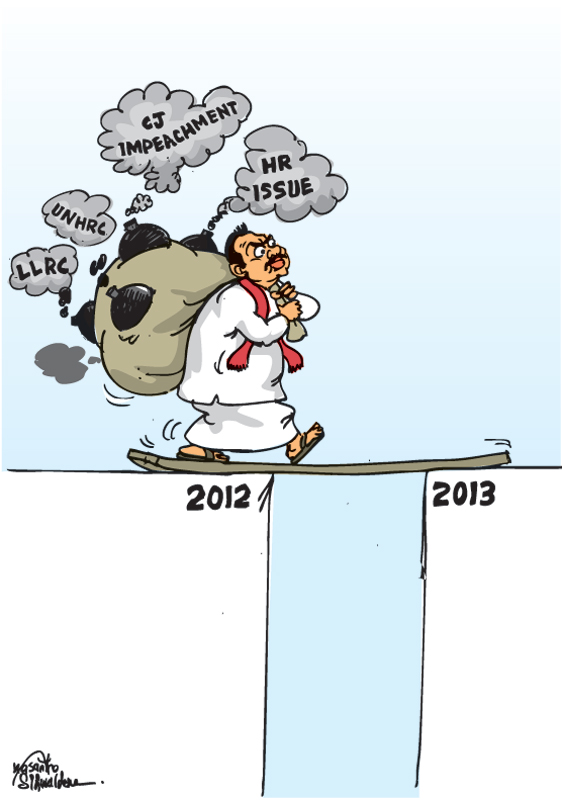

Impeachment crisis: Destiny of Lanka at stake

Arguably, the political system has also gone through a metamorphosis in more recent years. If one formidable political party at the centre picks on a ‘strongman’ to contest a district, it became customary for the rival party to select his or her opponent. They did not necessarily come from academia or with a professional background. The process spawned a relative drop in quality in the calibre of those who represented the voters. That is by no means to say there are no more men or women of wisdom. There are, but some have been relegated to the graveyard of the silenced. For some others, the stakes involved have struck a blow to principles. The choice before them is survival, both personal and political.

Arguably, the political system has also gone through a metamorphosis in more recent years. If one formidable political party at the centre picks on a ‘strongman’ to contest a district, it became customary for the rival party to select his or her opponent. They did not necessarily come from academia or with a professional background. The process spawned a relative drop in quality in the calibre of those who represented the voters. That is by no means to say there are no more men or women of wisdom. There are, but some have been relegated to the graveyard of the silenced. For some others, the stakes involved have struck a blow to principles. The choice before them is survival, both personal and political.

Sunday, December 30, 2012

= If the law enforcement process loses its independence, politicos might play the role of policemen and anarchy will prevail

= �President insists on going ahead with the move despite pleas by allies�for prorogation of Parliament

By Our Political Editor

Sri Lanka’s Parliament has functioned for more than 179 years though under different names at different times. That is from the time of the Legislative Council in 1833.

The laws they wrote in to the statutes and the contributions made by the learned members have gone into public record. Both, the members and the records that have lived the test of time were revered though some may have reflected diverse opinions.

Over the years, Sri Lanka’s political culture polarised into one of the ruling party and a main opposition being the key players. There were checks and balances though it was on a reducing scale. In recent years, the fact that a coalition of parties forming the United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA) is in governance with hardly any vibrant opposition is well known the world over. This week, the absence of a strong opposition became the lament among even key cabinet ministers from leftist parties. They are perhaps unmindful that their leader, President Mahinda Rajapaksa, should get part or more of the kudos. His deft manoeuvering has divided some political parties or united some factions in his favour.

Chief Justice Shirani Bandaranayake attending the Bodhi Pooja organised by a group of lawyers at the Kelaniya Raja Maha Viharaya this week. Pic by Indika Handuwala

Arguably, the political system has also gone through a metamorphosis in more recent years. If one formidable political party at the centre picks on a ‘strongman’ to contest a district, it became customary for the rival party to select his or her opponent. They did not necessarily come from academia or with a professional background. The process spawned a relative drop in quality in the calibre of those who represented the voters. That is by no means to say there are no more men or women of wisdom. There are, but some have been relegated to the graveyard of the silenced. For some others, the stakes involved have struck a blow to principles. The choice before them is survival, both personal and political.

Arguably, the political system has also gone through a metamorphosis in more recent years. If one formidable political party at the centre picks on a ‘strongman’ to contest a district, it became customary for the rival party to select his or her opponent. They did not necessarily come from academia or with a professional background. The process spawned a relative drop in quality in the calibre of those who represented the voters. That is by no means to say there are no more men or women of wisdom. There are, but some have been relegated to the graveyard of the silenced. For some others, the stakes involved have struck a blow to principles. The choice before them is survival, both personal and political.

When political parties were returned with overwhelming mandates, it became a tool for the government in power to tinker with the constitution. Such moves made the office of the Executive Presidency omnipotent. A later 18th Amendment to the Constitution not only degraded Parliament but also strengthened individual power of that office. Thus, it became the Executive President who appointed the Chief Justice, senior judges, the Police Chief and the Elections Chief among others. The role of the opposition became only advisory and they continue to refuse to participate in such a process. The Human Rights Commission and the Attorney General’s Department among others came under the presidency. Institutional power was thus weakened.

Yet, the institution these elected representatives belong, the Parliament, the supreme body remains sacrosanct. What they place on official record, like legislation they pass, remains for posterity though some may have become obsolete and the others amended. So are the findings of Parliamentary Select Committees (PSC) that are appointed to probe various issues of national importance. The findings in the form of a report have become a “Magna Carta” of sorts in the fields they delve in.

This is why the 1,575 page two-part report of the Parliamentary Select Committee that probed the impeachment charges against Chief Justice Shirani Bandarnayake is significant. Though only signed by the seven members of the ruling coalition, after the four opposition members walked out in protest on grounds that the process was not just and fair, it will still remain a record for both the public and future parliamentarians for generations to come. Fearful or comforting enough, it could form the yardstick or precedent for future parliamentary probes. More so in an environment where past reports or utterances are cited to back present practices and justify them. Such justifications have sometimes gone beyond simple logic or complex legalities. Read More