2017-05-01

2017-05-01

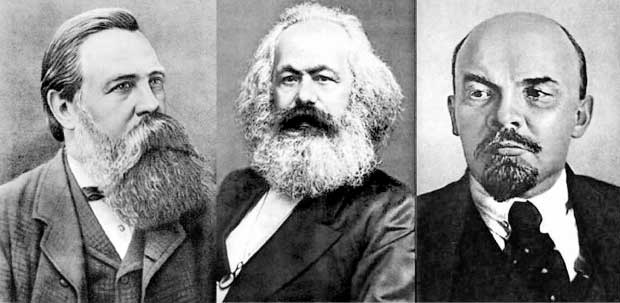

The eight-hour working day has its legacy in a long history of May Day protests. Over 150 years ago, in 1866, the first general congress of the International Workingmen’s Association, commonly known as the First International, resolved that the eight-hour working day would be one of the primary demands of the workers of the world.

Two decades later, militant demonstrations for an eight-hour working day in Chicago on May 1st, 1886 were brutally repressed by the police, leading to May First as a day of protest. Subsequently, the Second International,convened in 1889 on the centenary of the French Revolution called for May Day as an international day of workers’protests and solidarity.

In many parts of the world, including Sri Lanka, May Day is the largest annual day of protest. But its relationship to the eight-hour working day is hardly remembered after the onslaught of decades of neoliberal capitalism. Even worse, in this country today, May Day has little to do with workers’ rights. Instead, political parties, including those that are explicitly opposed to workers’ rights, use it as a show of strength. These demonstrations of political patronage continue even as all the hard-fought rights of workers are under attack.

Work in our Times

The industrial working class, which historically struggled for the eight-hour working day in Europe and the United States, makes up only a small fraction of labour in Sri Lanka. Furthermore, the formal sector, consisting of just 40% of the labour force in Sri Lanka,is steadily becoming informalised as it is being replaced by temporary workers, including those supplied by manpower agencies. Several recent strike actions demanding permanency, including the long strike of Telecom workers, which ended just a few weeks ago, and last year’s strike by the Jaffna Municipal Council garbage workers, reflects the growing informalisation of the labour force. Worryingly, this abominable employment practice is becoming common place in sectors where permanent employment was the norm for many decades.

Workers in the formal sector, including those who have permanent jobs, must do over-time work to earn a decent income to sustain their families. Engaging in over-time work out of necessity is a reversal of the long fought demand for an eight-hour working day, which has its basis in the idea that the worker’s day should entail no more than eight hours of work with eight hours for leisure and eight hours for rest. Work today is neither regular nor limited, but depend on the whims of the capitalist system and its drive to maximise profits. When people work from morning till night, or take up multiple jobs, or live in fear of losing their temporary jobs, they can no longer be citizens participating in a democracy. Even time to struggle for decent working conditions are denied, as their time is fully consumed in working to survive.

The large majority of our people continue to work in agriculture and fisheries, or plantations where work is dwindling, or eke out a precarious livelihood in urban and rural informal production and services. With falling incomes, more and more of them are compelled to find low-paying urban work, migrate to the Middle East or desperately seek multiple jobs. Work for our people then is increasingly becoming precarious with falling wages, lack of job security and no limits on exploitation.

Powerful Social Barrier

J. R. Jayewardene set the terms for successive governments’ engagement with workers and their trade unions by brutally crushing the general strike of July 1980. The trade union movement is yet to recover from that blow. Today, just 10% of the labour force are trade union members. While the labour laws themselves were not drastically changed with the adoption of open economic policies in 1977, the laws are rarely implemented by the state in the context of a weak labour movement. Set up to address workers issues,the Labour Department functions as an ‘Employers Department,’ as business circumvents labour laws with ease. To make matters worse, the Government now wants to change the labour laws, making it even easier for businesses to hire and fire, and legally extend the working day. Indeed, the idea of a social contract, between the state, business and labour, which also underpins the principles of the International Labour Organisation (ILO), no longer holds. There is strong collusion between the state and business, and the ILO itself seems to have surrendered to the interests of big business, the World Bank and the IMF. All of them together today are on the offensive to remove any laws that mayprotect the working people in Sri Lanka.

One hundred and fifty years ago, Karl Marx, who was instrumental in initiating the First International and its eight-hour working day campaign,said this about labour laws: “For ‘protection’ against the serpent of their agonies, the workers have to put their heads together and, as a class, compel the passing of a law, an all-powerful social barrier by which they can be prevented from selling themselves and their families into slavery and death by voluntary contract with capital. In the place of the pompous catalogue of the ‘inalienable rights of man’ there steps the modest Magna Carta of the legally limited working day, which at last makes clear ‘when the time which the worker sells is ended, and when his own begins’.” (Capital, Volume 1, p.416)

Here Marx is critical of mere lists of rights, as with human rights in our day, that are rarely implemented. Rather, he is calling on workers to extract a law to limit the working day as part of building a powerful social barrier against the ravages of capital. The current attack on the labour regime in Sri Lanka, can only be understood as an attempt to destroy the remnants of such a social barrier, and reduce workers to slaves at the mercy of capital.

Season of Protests

Laws mean nothing without the power and backing of people. The working people themselves must compel the Government to ensure that labour laws are not watered down and are implemented to the word. Yet the formal workers on their own, for whom the labour laws were made, cannot guard the labour regime,much less build a powerful social barrier.

The great challenge for the working people is to build a broad alliance, of farmers, fisher-folk, estate workers, urban and rural wage workers, factory and service sector workers, and students and teachers. The people have everything to lose, from free education and healthcare, to their resources and entitlements, to all the necessities of life for which they have worked and struggled. To avoid that the citizenry must wage major democratic battles tocreate a powerful social barrier to withstand the attack by the nexus of the state, business and their imperial patrons in the form of global capital and donor agencies.

There is little today to celebrate in the May Day rallies by political parties that have sold the working people for the profit of capital. If there is one lesson for state officials, Colombo’s elite and middle class liberals to learn from the Meethotamulla garbage slide disaster that killed scores of people few a weeks ago, it is the importance of listening to protests before tragedy unfolds. The current season of protests – the farmers and fisher-folk protesting for land and access to the seas in the North, the students protesting against SAITM and the privatisation of education and healthcare, and numerous other trade union agitations and strikes – are signs of the people reclaiming democracy.Such protests are also elements of a powerful social barrier for a just and equal society