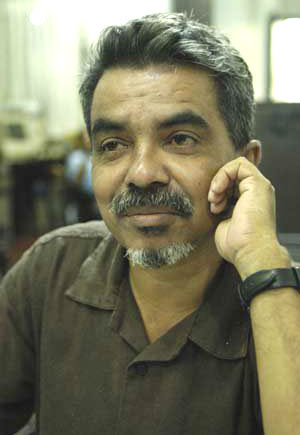

Thavarasa Utharai son Jadusan, 14 years, holds a picture of his missing father and mother. He last saw his father in March 2009. Credit: Amantha Perera/IPS

PAVAKODICHENNAI, Sri Lanka, Oct 29 2015 (IPS) - Thavarasa Utharai’s most treasured belongings are stuck inside several plastic bags and tucked within old traveling bags.

Inside, wrapped in more plastic sheets, are old fading photographs, scrap books, legal documents and even some old bills. These are the only processions the 36 year old mother of two has to show of her husband. He went missing on March 20, 2009 while returning home after tending to his cattle. No one really knows what happened to him.

“They took him, I know they did, I know the person who did it also,” Utharai says of suspected abductors who she says were linked to government military. The abduction took place as a three decade old bloody civil conflict was drawing to an end and government forces were poised to achieve a decisive military victory over the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). The separatist LTTE had fought successive Sri Lankan governments to achieve a separate state for the country’s minority Tamils like Utharai.

Utharai hails from the remote village of Pavakodichennai, in the eastern Batticaloa District about 350 km from the capital Colombo. But distance and lack of public utilities like transport and a functioning public service have not prevented her from seeking justice. She has sought the intervention of police, a Presidential Commission and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to gain any morsel of information on her husband. So far she has hit a blank wall, except when an officer with Criminal Investigation Department suggested that if she register her husband as deceased her family would be eligible for Rs 100,000 (700 dollars) in compensation.

“Why should I? I will seek the truth, I owe it to him,” the slightly built woman says with a feisty tone.

Her circumstances however are not rare in the former conflict-zone. Tens of thousands are still looking for their missing loved ones six years after the guns fell silent. The number of the missing has remained contentious since the war ended. A Presidential Commission on Missing Persons that has been conducting interviews since 2013 has so far received over 20,000 complaints, including over 5,000 of missing members of government forces. The ICRC, which has been registering missing persons since 1990, has recorded 16,064 cases. An Advisory Panel to the UN Secretary General put the death toll during the final phase of the war at 40,000. Research by the advocacy group University Teachers for Human Rights from northern Jaffna increased that figure to 90,000.

“It really does not matter how high or how low these figures are, for each family it is vital that they get to know what happened to their loved ones,” Vallipuram Amalanayagni said. She has been searching for her husband since he went missing in February 2009. He went missing while at his paddy field.

Amalanayagni also acts as a community leader for families of the missing. She says the last six years have been some of the hardest in her life. “We were hounded like criminals because we looked for our family members.”

As the then Mahinda Rajapaksa government fought off wave after wave of international scrutiny on the conduct of the final phase of the war, it did not encourage any action that could fuel international pressure – looking for the missing or tabulating them was one of them. During the last months of his administration, Rajapaksa loosened the grip a bit but not by a lot.

All that changed in January this year, when a new president, Maithripala Sirisena, took office. The new government has renewed engagement with the UN and has pledged to strengthen efforts to trace the missing and provide compensation.

It will set up a missing persons office and also issue Certificates of Absence. Last week it also released a

report by a Presidential Commission looking into allegations of abductions and disappearances. The commission has acknowledged that disappearances did take place while persons were in military custody and that military linked groups were involved in abductions.

“This is not a political gimmick, we are serious about what we have set out to do,” Minister Rajitha Senarathana, the cabinet spokesperson told IPS.

The minister said that investigating the thousands of missing cases was a pledge that President Sirisena, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremasinghe and their loyalists made while they campaigned to oust the Rajapaksa administration

“For a nation to heal we must know the truth, however difficult and uncomfortable it may be,” Senarathana said.

Given the media hype, expectations have also risen that there could be fast tracked action. But Sri Lanka watchers caution not to raise hopes too high and to give the current government enough time to feel politically secure.

“It would be slow progress, the government has shown its inclination that it wants to act on these, it has international support right now, but it would need time to convince everyone,” Jehan Perera, Executive Director National Peace Council, a national advocacy body.

Diplomatic sources in Colombo also say that the Sirisena government is still wary of the Rajapaksa factor and the former president’s core support base of ultra-nationalists from the Sinhala majority.

For the families of the missing, there is at least a new ray of hope. “Some of us have been looking for loved ones for decades, imagine living without any kind of knowledge of your husband for over a decade, that is a terrible tragedy, at least now there should be closure,” Amalanayagni said.

(End)