Want smart analysis of the most important news in your inbox every weekday, along with other global reads, interesting ideas and opinions to know? Sign up for the Today’s WorldView newsletter.

We don’t know how many people have died since Cyclone Idai made landfall last Thursday on the coast of Mozambique before barreling west into Zimbabwe and Malawi. Aerial photography and drone footage have shown the apocalyptic scenes left in the cyclone’s wake: Fields of crops were ruined, rising floodwaters tore bridges off their moorings, mudslides smashed roads and whole villages were swept away. Survivors found themselves trapped on new “islands,” surrounded by the brackish waters that obliterated their homes.

We don’t know how many people have died since Cyclone Idai made landfall last Thursday on the coast of Mozambique before barreling west into Zimbabwe and Malawi. Aerial photography and drone footage have shown the apocalyptic scenes left in the cyclone’s wake: Fields of crops were ruined, rising floodwaters tore bridges off their moorings, mudslides smashed roads and whole villages were swept away. Survivors found themselves trapped on new “islands,” surrounded by the brackish waters that obliterated their homes.

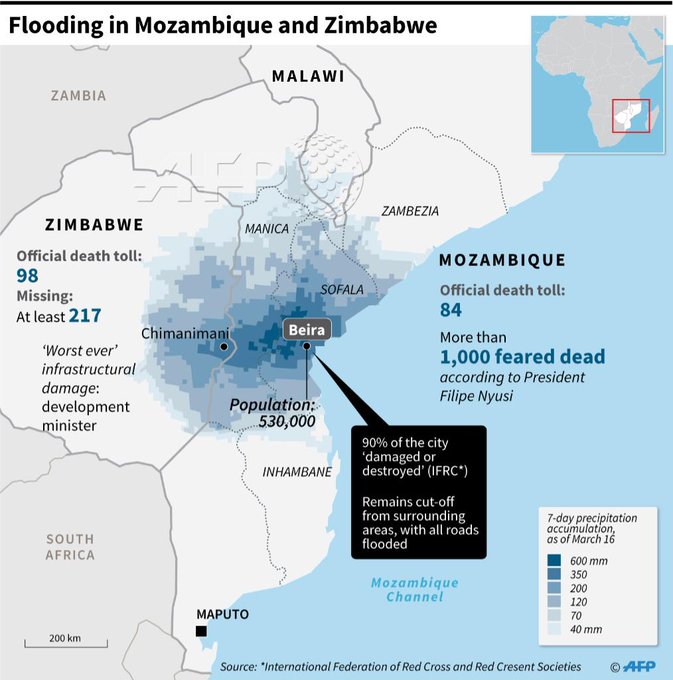

The United Nations estimated that more than 2.6 million people are in need of immediate assistance. Aid officials believe the tropical storm damaged or destroyed some 90 percent of the Indian Ocean port of Beira, Mozambique’s fourth-largest city. Though the country’s authorities placed the official death toll at under 100 so far, President Filipe Nyusi spoke to local media after flying over affected areas in a helicopter and said that “everything indicates that we can have a record of more than 1,000 dead.” In Zimbabwe, the official death toll stood at 98; in Malawi, it’s at 56 — but the actual figures may take months to determine.

“The region affected by Idai is one of the poorest in the world,” wrote my colleague Max Bearak, who was en route to the ravaged city on Wednesday. “Infrastructure was already lacking, and the storm has destroyed key public institutions like hospitals and water sources.” Beira is a major entry point for food and gas inland; its paralysis raised fears of possible shortages across the region at a time when resources are already deeply strained.

Rescue efforts were hampered by collapsing infrastructure, poor telecommunications and heavy rains that continued through Tuesday. A giant storm surge, reported to be above 19 feet in some areas, transformed Beira — a city of half a million people — into a woeful waterworld, largely cut off from the rest of the country. According to the New York Times, the main highway into the city is impassable, while debris and toppled trees clog up other secondary roads.

“Everything is destroyed, everything,” said Deborah Nguyen, a World Food Program official, to The Post. “When I got here on Sunday, you could see the tops of palm trees in rural areas. Now it is just an inland ocean. The rain isn’t stopping anytime soon.” Her organization is nevertheless still attempting to airdrop food to stranded communities.

If the death tolls rise to the levels suggested by Nyusi and others, then Idai may prove an epochal event. “If these reports, these fears, are realized, then we can say that this is one of the worst weather-related disasters — tropical cyclone-related disasters — in the Southern Hemisphere,” Clare Nullis, a spokeswoman for the World Meteorological Organization, told reporters.

Yet the scale of the calamity has yet to fully register around the world, with news of the storm’s destructive path only making major headlines almost a week after it made landfall. “There’s a sense from people on the ground that the world still really hasn’t caught on to how severe this disaster is,” Matthew Cochrane, a spokesman for the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, said at a briefing in Geneva.

That’s unfortunately not surprising, given the extent to which disasters in areas of the world like sub-Saharan Africa tend to get short shrift in the global conversation. In a reflection on the “erasure of African tragedy,” Atlantic writer Hannah Giorgis pointed to the implicit bias beneath some of the initial reporting around another recent calamity — the crash of an Ethiopian Airlines jet and the death of all the passengers and crew aboard.

“Both the impulse to question the largest African air carrier’s credibility and the hyper-focus on Western passengers are consistent with the pervasive, long-running Western disdain for — or simple inability to empathize with — people of African descent,” wrote Giorgis.

It’s also true that onlookers, especially those far away, get numbed by tragedies of this scale. “For decades, social scientists have documented a troubling quirk in human empathy: People tend to care more about the suffering of single individuals, and less about the pain of many people,” Jamil Zaki of Stanford University wrote last year following a devastating tsunami in Indonesia that killed hundreds of people and displaced tens of thousands more. “Such ‘compassion collapse’ is morally backwards — dozens or hundreds of people, by definition, can lose more, fear more, and hurt more than any one of us; human concern should scale with the amount of pain in front of us. Instead, it dries up.”

But, now, even the news releases of aid agencies carry chilling anecdotes: Save the Children, for example, warned of the perils facing some 2,500 children and their families, stuck in the town of Buzi in Mozambique’s Sofala province. By Tuesday, there were fears that rising floodwaters would wholly submerge the town.

The response to the unfolding disaster is also straining a beleaguered humanitarian response system that’s already facing funding shortfalls. And long after the floodwaters recede, governments in the region will have to reckon with a grave reality — that extreme weather events like this cyclone will be more common in the years to come, as the warming of the planet continues to affect global climate patterns.

An index compiled by the World Bank ranked Mozambique as the African nation that is third-most exposed to weather-related disasters, including drought, cyclones and the lethal epidemics that often follow in their wake.

“As the effects of climate change intensify, these extreme weather conditions can be expected to revisit us more frequently," Muleya Mwananyanda, Amnesty International’s deputy regional director for Southern Africa, said in a statement. “The devastation wrought by Cyclone Idai is yet another wake-up call for the world to put in place ambitious climate change mitigation measures.”

Want smart analysis of the most important news in your inbox every weekday, along with other global reads, interesting ideas and opinions to know? Sign up for the Today’s WorldView newsletter.