Brigadier Priyanka Fernando: A (Suggested) Wider Context

The throat-cutting gesture by Brigadier Priyanka Fernando in London

Response of the (Sinhalese) army to the (Sinhalese) JVP uprising

“The fault is not in our stars; not in Fate, God or the gods but in us, human beings” ~ (Adapted from Shakespeare’s ‘Julius Caesar’, Act 1, scene 2, lines 141-2).

The recent furore over the throat-cutting gesture by Brigadier Priyanka Fernando in London aimed at demonstrating Tamils led me to the subject of soldiers in general. That the Brigadier pointed to his army insignia and then made the gesture suggests he believes this is what soldiers do: they kill. The gesture can be understood as a synecdoche standing for different forms of violence, murder included.

The word “soldier” etymologically has its roots in “payment”, and payment is related to “professional”. A soldier is a professional; someone paid to endanger his own life while endangering those of others, be they soldiers or hapless civilians – since language is used both to communicate and to conceal, civilian casualties are referred to a ‘collateral damage’. A soldier is paid to attack or to defend by attacking: the Israeli army is named the Defence Force. Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), in his Leviathanfamously described human life in nature as short and brutish, there being a propensity in humans to be aggressive; to invade, rob and take possession. That being the case, we need an authority. But authority has no authority without the power of enforcement; in short, without armed men and women. Given human nature, society needs armed personnel ready to carry out orders. (Of course, many of us have no inclination to dispossess and dominate others and, if such negative impulses do arise, we restrain them: contrary to Hobbes, John Locke, 1632-1704, argued that we are rational creatures.

Let me begin by asking why men and women volunteer to join the armed forces, thus placing their lives in jeopardy. Many years ago, when the war against the Tamil Tigers was intense, a Sinhalese friend told me his wife was daily and bitterly blaming him for having allowed both their sons to enlist. But, he explained, when they joined, there was no war: “My sons don’t have qualifications, and the armed forces mean food, shelter and salary.” Thomas Hardy in a poem, ‘The man he killed’, imagines himself to be someone who had joined the army because he was unemployed and poor. Perhaps, the man he had just killed was like him, unemployed and poor. Poverty is a downward spiral: perhaps the man, in desperation, had sold his tools and now without tools, he can’t offer his services as a worker with a skill to sell. Of course, there are other reasons why individuals enlist: patriotism, family influence, an immature attraction to uniform, weapons and parades etc. Nor must one forget idealism and the self-sacrifice that goes with it. For example, individuals from Europe and the USA (Ernest Hemingway; Nobel Prize for Literature) volunteered to fight in the Spanish Civil War. Earlier, Lord Byron died (though indirectly) supporting the cause of Greek independence. I don’t cite Sri Lankan examples because some readers are prone to misreading and misunderstanding or, easily excited, focus on trivialities and irrelevancies.

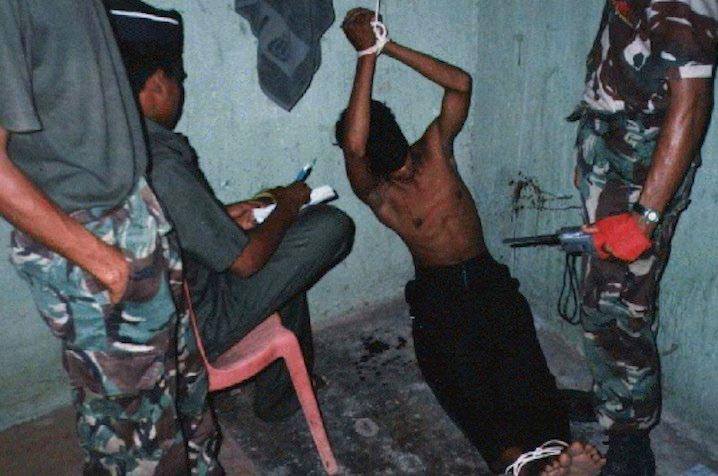

An erstwhile friend of mine, because he was a university graduate, was able to join the army as a trainee-officer but I suppose the majority by far join at the lowest rank and then are hammered into shape as soldiers. It is a tough – one would say brutal – process graphically portrayed in ‘An Officer and a Gentleman’ (1982). I believe the film is still screened to soldiers in various armies. Why trainee soldiers are bullied and insulted, treated “worse than dirt”, I don’t know but presume it has two reasons: to toughen them up and, secondly, to weed out those who cannot be made sufficiently tough and callous. The armed forces being an instrument of government enforcement, its members cannot be soft-hearted and sensitive. On the contrary, they must be ready and willing to be brutal. They are the creation of the state, are meant to serve the state, and reflect both state and the people in whose name and on whose behalf they act. Brutalised in training, many become brutal and the ‘argument’ of force becomes their main, if not only, answer. Harshness is normality. Bullied by those higher in rank, the lowest have only civilians to bully in turn. Even those who have reached high military rank presumably came through a harsh system and carry its marks. The word “callous” now meaning insensitive and unsympathetic (therefore cruel) is derived from a hardening of the skin through repeated friction. In that sense, a callous is a self-protective mechanism.