Gunaratne’s Road To Nandikadal

By Charles Ponnuthurai Sarvan –January 17, 2017

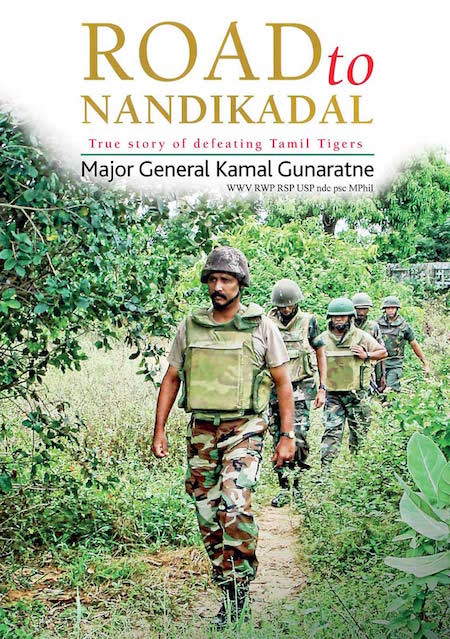

Book Review – Major General Kamal Gunaratne, Road to Nandikadal: True story of defeating Tamil Tigers, Colombo, 2016.

Epigraph: Those who have power in the present, control the story of the past; and those who control the past, shape the future. ~ (Adapted from Orwell’s dystopian novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four.)

Epigraph: Those who have power in the present, control the story of the past; and those who control the past, shape the future. ~ (Adapted from Orwell’s dystopian novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four.)

As readers well know, the word “prejudice” comes from to pre-judge; to judge or form an opinion without first independently examining the evidence. Going by what I had read about this book, I confess I was prejudiced but, having gone through it, my former opinion was confirmed. “Pre-judice” became “post-judice”, an instance of postjudice confirming prejudice. (Or is the latter – consciously or subconsciously – conditioning the former? After all, as Heidegger noted, even objectivity is judged by a subjective self.) To express it bluntly, I think this on several counts is a very poorly produced work. Yet it has proved popular with the first-printing of the English translation being immediately sold out – a reaction not without its significance in what it suggests about the reading-public. In what follows I attempt to explain the grounds for my opinion, fully accepting that it is only one, fallible, “reading”; that others will have different approaches and evaluations: disagreement and the resulting variety of readings are to be welcomed.

To begin with, there are many grammatical mistakes, lapses in expression, not to mention linguistic infelicity. However, the responsibility here is not that of the good Major General but of his translator. No doubt, the work would have benefitted from editorial oversight. (How the text reads in the original ‘Sinhala’, I don’t know.) The author’s excursions into figurative language result in absurd images such as Indian fighter-jets being seen as hooligans raping Sri Lankan airspace: raping airspace? This leads me to another regrettable feature, that of the author’s emotionalism: I could feel hot blood coursing through my body like an electric shock (p. 107). I would have crushed the aircraft and flushed them down the toilet. (Again: flush aircraft down a toilet? It’s ludicrous.) Wasn’t this “a rape of our beloved Motherland”? (p. 108); driving a dagger through the hearts of Buddhists (p. 421) etc. One wonders whether the Major General had in mind a particular segment of Sinhala-readers who would admire and applaud such an inflammatory, vulgar, style. If so, it’s not a compliment to them. His emotionalism leads to an extreme and simplistic contrast between the LTTE (the most brutal terrorists, ruthless, cruel, barbaric murderers, maniacal attackers) and his soldiers who go into battle with a loaded weapon in one hand and a book on human-rights in the other (p. 2), “the finest and most gallant soldiers on earth”. No doubt, there’s loud applause, and the heedlessly galloping Major General needn’t pause to clarify with which other armies, world-wide, the comparison is being made, nor the criteria for his comparative evaluation. Readers are not expected to stop, reflect and scrutinise independently but to be swept along with the tide of high patriotic passion.

To begin with, there are many grammatical mistakes, lapses in expression, not to mention linguistic infelicity. However, the responsibility here is not that of the good Major General but of his translator. No doubt, the work would have benefitted from editorial oversight. (How the text reads in the original ‘Sinhala’, I don’t know.) The author’s excursions into figurative language result in absurd images such as Indian fighter-jets being seen as hooligans raping Sri Lankan airspace: raping airspace? This leads me to another regrettable feature, that of the author’s emotionalism: I could feel hot blood coursing through my body like an electric shock (p. 107). I would have crushed the aircraft and flushed them down the toilet. (Again: flush aircraft down a toilet? It’s ludicrous.) Wasn’t this “a rape of our beloved Motherland”? (p. 108); driving a dagger through the hearts of Buddhists (p. 421) etc. One wonders whether the Major General had in mind a particular segment of Sinhala-readers who would admire and applaud such an inflammatory, vulgar, style. If so, it’s not a compliment to them. His emotionalism leads to an extreme and simplistic contrast between the LTTE (the most brutal terrorists, ruthless, cruel, barbaric murderers, maniacal attackers) and his soldiers who go into battle with a loaded weapon in one hand and a book on human-rights in the other (p. 2), “the finest and most gallant soldiers on earth”. No doubt, there’s loud applause, and the heedlessly galloping Major General needn’t pause to clarify with which other armies, world-wide, the comparison is being made, nor the criteria for his comparative evaluation. Readers are not expected to stop, reflect and scrutinise independently but to be swept along with the tide of high patriotic passion.

To make a minor but not insignificant point, Major General Gunaratne who makes clear his fervent commitment to Buddhism writes: “I lit the traditional oil lamp at an auspicious time given by my wife who had consulted an astrologer” (p. 644). This is nothing but primitive superstition. (“Primitive” is here intended in the sense of “primordial”.) Superstition is the product of human ignorance and fear. In turn, the emotion of fear spawns hatred and cruelty. But Buddhism (besides compassion for all beings) rests on pillars such as rationality and morality. Belief in astrology is ‘primitive’ superstition, part of the weeds, stones and cobwebs the Buddha attempted to clear away. The question prompts itself: Is the Major General a true Buddhist or does he remain a prisoner of superstition, and of empty ritual, however fervent?

But more is at stake here than lapses in language, style, emotionalism and primitive superstition. Nandikadal can be seen as a Mahavamsa of the Eelam War: I use the indefinite article “a” because there must be other Mahavamsa-type works on the war in Sinhala being enthusiastically received. Scholars (most of them Sinhalese) have investigated the Mahavamsa and established that it is an imaginative construct – which Nandikadal surely isn’t. So the comparison I suggest between the ancient and recent text is based on factors such as bias, one-sidedness, anger, hatred and, above all, the effect the work will have on the beliefs and feelings of the populace. Even those who admit that the Mahavamsa is a story are affected by it subconsciously. (Gunaratne refers to Vihara Maha Devi, the mother of King Dutugamunu, as “the greatest heroine in our history”, confident readers know the story and will respond appropriately.) Stories from the Mahavamsa are related to children at home, in school and in the temple. (I recall a Tom Paxton Vietnam ‘protest-song’: “What did you learn in school today, dear little boy of mine?” The son answers he learnt that our government is always right, and that war is good.) The uncritical will read this book, particularly in Sinhala, and will carry its marks on their mind. To use in quite another context words from the poem ‘Missing Dates’ by Ezra Pound, “Slowly the poison the whole blood stream fills… / The waste remains, the waste remains and kills”.