Our Parliament has increasingly become a forum for the ragtag and bobtail, mediocre and the vulgar; a relatively easy path for a social step-up and financial nirvana

To say that in our times all public institutions and office, professions and honours have been diminished will not be an exaggeration. On the contrary, considering the overall lack of credibility in all these things today, it may be said that it is an understatement, when after all many of them have now been rendered meaningless, representing the very opposite of what they are meant to be.

There is hardly anyone who will speak for the presidency, the highest office in the land. It took only six incumbents and 40 troubled years to completely disillusion the nation, to weary of an office associated with a huge potential for abuse of power, nepotism and corruption in various forms.

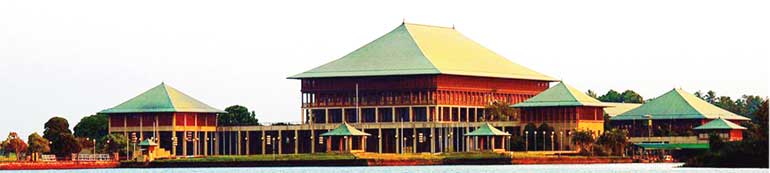

Our Parliament has increasingly become a forum for the ragtag and bobtail, mediocre and the vulgar; a relatively easy path for a social step-up and financial nirvana. The Judiciary appears overwhelmed by the enormity of the task before it, again, with neither dazzle nor brilliance. As to our over-staffed yet under-performing government departments; their monopolistic hold valid only because so little is expected of them in terms of performance.

The malaise is not confined to the Government, as the saying goes; so within, so without. If the Hippocratic Oath is suggested to a present day doctor, he will feign total ignorance. The once sacred professional codes (and standards) for the various professions have now become mere showpieces, little understood, hardly evoked. Promotions, recognitions, honours only go by political favour. As a result, presently most professionals are in part-time politics.

A middling lawyer goes to his party boss, the President, with a plea to be appointed a President’s Counsel. The President is in an indulgent mood and grants the request of the humble lawyer. Sometime later, there is a constitutional controversy. Our obliging President’s Counsel promptly expresses an opinion on the Constitution which is favourable to his patron. Even the President holds out the opinion of the President’s Counsel as one coming from a person recognised by the State as an eminent jurist. What he lacked earlier; seriousness, maturity, intelligence have been conferred on him by Presidential decree!

It will be a mistake to think that such happenings are only of recent origin. In 1948, when the managing of our affairs was handed back to us, the world was very different to the one we were familiar with, pre- 1815. With independence came constitutions, laws, elections, parliaments, government departments, and a plethora of other new and exciting things. To sit behind a desk and push a pen was prestigious.

It will be a mistake to think that such happenings are only of recent origin. In 1948, when the managing of our affairs was handed back to us, the world was very different to the one we were familiar with, pre- 1815. With independence came constitutions, laws, elections, parliaments, government departments, and a plethora of other new and exciting things. To sit behind a desk and push a pen was prestigious.

Nascent capitalism in the colony had opened undreamt of paths to riches to all and sundry. Office and honours did not depend on your birth anymore. These honours came with a lot of pomp and pageantry, sometimes even a trip to the Buckingham palace was included. In to this new world of infinite possibilities, we plunged in with the gusto of the recent convert , a melee of “nobodies” as well as “somebodies”, chasing behind the goodies and the shinning toys with unashamed abandon. Self-seeking, dissolute, former colonials saw no bounds in their quest for honours. It was the “unspeakable in pursuit of the uneatable”; Oscar Wilde’s famous description of fox hunting, relived.

We cannot do better than Tarzie Vittachi, one of the most acclaimed English journalists of the era, in describing the temper of the time:

“Englishmen and Englishwomen had to risk their lives over and over again during the war to win recognition. Odette Churchill, one of the most courageous women to serve in the French underground had to serve her candidature in a torture chamber before she was made an MBE. But in Asia, an MBE was generally looked upon with the same disdain that a brontosaurus might have shown to a worm wriggling out of the primeval ooze. At any cocktail party in Karachi, Colombo or Kuala Lumpur you couldn’t spit your olive-seed without potting a couple of OBEs.

“Elsewhere the road to a knighthood was generally long, narrow and straight. It took a Len Hutton, a Jack Hobbs and a Don Bradman to earn the first knighthoods for cricket. A man had to be an Olivier, a Reed or a Gielgud to win a knighthood for contribution to drama, and a Cockroft or a Penny for similar recognition of achievements in nuclear science. But in South Asia it was not impossible to become a KBE for supplying cakes, sandwiches and peach Melbas at cut rates for government parties.

“If you hung around long and often enough on the verandahs of the residences of the great, making yourself generally available for fetching and carrying, there was a fair chance that you would end up with a knighthood. It was really a return to the old courtly tradition of honouring courtiers ( who were usually people pursuing social prestige with the dog-eyed devotion more usual ,nowadays, in those who pursue political careers) who had nothing better to do than to hang around the palace precincts hoping that a crumb would be thrown their way. In the 1950 South Asian context you had to be useful to the Prime Minister to get noticed when the Honours list was due for decision

“Was the Buckingham Palace ignorant of this hectic Asian commerce in imperial honours? Did the Commonwealth Relations Office never realise that knighthoods were showering down South Asia faster than the autumn leaves in Vallambrosa? Was it possible that no one in Whitehall was alarmed at the possibility that there would soon be a glut in the honours market and that the Queen’s medals were in danger of becoming as distinct as screw nails in a junkyard?

“They all knew. The honours list recommended by the new free and equal Commonwealth of Nations always provided material for many hours of helpless mirth among the civil servants in Whitehall through whose hands it passed. But the dominions were extremely sensitive to any slights from London. No one dared to say a word openly.

“On one or two occasions a British Governor General whose job it was to ‘ forward’ his prime Ministers list of recommendations to the palace , tried to whisper a word or two about the necessity of maintaining high standards of capacity and dignity in the Honours List.

“He asked, oh-so-tentatively, whether it would not be advisable to drop Mr. Distiller’s, Mr. Hotelier’s and Mr. Pill-Pusher’s nominations for knighthoods since their unsavoury reputations had penetrated even the marble halls of the Government House. He must have wished he had never spoken. The prompt and devastating retort was: ‘do you want to go back to doing your own washing-up in South Kensington?’” (The Brown Sahib – Tarzie Vittachi 1962)

A middling lawyer goes to his party boss, the President, with a plea to be appointed a President’s Counsel. The President is in an indulgent mood and grants the request of the humble lawyer. Sometime later, there is a constitutional controversy. Our obliging President’s Counsel promptly expresses an opinion on the Constitution which is favourable to his patron. Even the President holds out the opinion of the President’s Counsel as one coming from a person recognised by the State as an eminent jurist. What he lacked earlier; seriousness, maturity, intelligence have been conferred on him by Presidential decree!

It will be a mistake to think that such happenings are only of recent origin. In 1948, when the managing of our affairs was handed back to us, the world was very different to the one we were familiar with, pre- 1815. With independence came constitutions, laws, elections, parliaments, government departments, and a plethora of other new and exciting things. To sit behind a desk and push a pen was prestigious.

It will be a mistake to think that such happenings are only of recent origin. In 1948, when the managing of our affairs was handed back to us, the world was very different to the one we were familiar with, pre- 1815. With independence came constitutions, laws, elections, parliaments, government departments, and a plethora of other new and exciting things. To sit behind a desk and push a pen was prestigious.Nascent capitalism in the colony had opened undreamt of paths to riches to all and sundry. Office and honours did not depend on your birth anymore. These honours came with a lot of pomp and pageantry, sometimes even a trip to the Buckingham palace was included. In to this new world of infinite possibilities, we plunged in with the gusto of the recent convert , a melee of “nobodies” as well as “somebodies”, chasing behind the goodies and the shinning toys with unashamed abandon. Self-seeking, dissolute, former colonials saw no bounds in their quest for honours. It was the “unspeakable in pursuit of the uneatable”; Oscar Wilde’s famous description of fox hunting, relived.

We cannot do better than Tarzie Vittachi, one of the most acclaimed English journalists of the era, in describing the temper of the time:

“Englishmen and Englishwomen had to risk their lives over and over again during the war to win recognition. Odette Churchill, one of the most courageous women to serve in the French underground had to serve her candidature in a torture chamber before she was made an MBE. But in Asia, an MBE was generally looked upon with the same disdain that a brontosaurus might have shown to a worm wriggling out of the primeval ooze. At any cocktail party in Karachi, Colombo or Kuala Lumpur you couldn’t spit your olive-seed without potting a couple of OBEs.

“Elsewhere the road to a knighthood was generally long, narrow and straight. It took a Len Hutton, a Jack Hobbs and a Don Bradman to earn the first knighthoods for cricket. A man had to be an Olivier, a Reed or a Gielgud to win a knighthood for contribution to drama, and a Cockroft or a Penny for similar recognition of achievements in nuclear science. But in South Asia it was not impossible to become a KBE for supplying cakes, sandwiches and peach Melbas at cut rates for government parties.

“If you hung around long and often enough on the verandahs of the residences of the great, making yourself generally available for fetching and carrying, there was a fair chance that you would end up with a knighthood. It was really a return to the old courtly tradition of honouring courtiers ( who were usually people pursuing social prestige with the dog-eyed devotion more usual ,nowadays, in those who pursue political careers) who had nothing better to do than to hang around the palace precincts hoping that a crumb would be thrown their way. In the 1950 South Asian context you had to be useful to the Prime Minister to get noticed when the Honours list was due for decision

“Was the Buckingham Palace ignorant of this hectic Asian commerce in imperial honours? Did the Commonwealth Relations Office never realise that knighthoods were showering down South Asia faster than the autumn leaves in Vallambrosa? Was it possible that no one in Whitehall was alarmed at the possibility that there would soon be a glut in the honours market and that the Queen’s medals were in danger of becoming as distinct as screw nails in a junkyard?

“They all knew. The honours list recommended by the new free and equal Commonwealth of Nations always provided material for many hours of helpless mirth among the civil servants in Whitehall through whose hands it passed. But the dominions were extremely sensitive to any slights from London. No one dared to say a word openly.

“On one or two occasions a British Governor General whose job it was to ‘ forward’ his prime Ministers list of recommendations to the palace , tried to whisper a word or two about the necessity of maintaining high standards of capacity and dignity in the Honours List.

“He asked, oh-so-tentatively, whether it would not be advisable to drop Mr. Distiller’s, Mr. Hotelier’s and Mr. Pill-Pusher’s nominations for knighthoods since their unsavoury reputations had penetrated even the marble halls of the Government House. He must have wished he had never spoken. The prompt and devastating retort was: ‘do you want to go back to doing your own washing-up in South Kensington?’” (The Brown Sahib – Tarzie Vittachi 1962)