How child sexual abuse became a family business in the Philippines

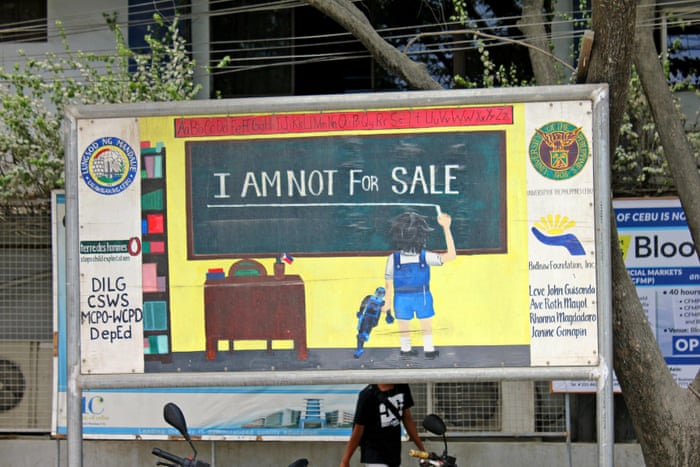

Rescued children in the playroom of the child protection unit at Philippine General hospital. Photograph: Andy Brown/Unicef Philippines--An anti-child abuse sign by a school in Cebu. Photograph: Oliver Holmes for the Guardian

A rescued child plays with a doll at the Philippine General hospital. Photograph: Andy Brown/Unicef Philippines

Tens of thousands of children believed to be victims of live-streaming abuse, some of it being carried out by their own parents

When Philippine police smashed into the one-bedroom house, they found three girls aged 11, seven and three lying naked on a bed.

At the other end of the room stood the mother of two of the children – the third was her niece – and her eldest daughter, aged 13, who was typing on a keyboard. A live webcam feed on the computer screen showed the faces of three white men glaring out.

An undercover agent had infiltrated the impoverished village two weeks before the raid. Pretending to be a Japayuki, a slang term for a Filipina sex worker living in Japan, she had persuaded a resident to introduce her to the children, who played daily in the gravel streets.

Her guise was intended to put them at ease, to show them she worked in the same industry; she was one of them. She became close to the eldest, referred to as Nicole although that is not her real name. After a few days of chatting, Nicole causally told the agent about their “shows”.

“It was the first time we heard of parents using their children,” said the middle-aged woman.

Authorities considered that operation in 2011 to be a one-off case. But the next month, another family was caught in the same area. Then more cases of live-streaming child abuse appeared in different parts of the Philippines.

Now, the United Nations says, there are tens of thousands of children believed to be involved in a rapidly expanding local child abuse industry already worth US$1bn.

In some areas, entire communities live off the business, abetted by increasing internet speeds, advancing cameraphone technology, and growing ease of money transfers across borders.

And while perpetrators used to download photos and videos to their hard drives – providing authorities with a virtual paper trail and usable evidence – criminals have found anonymity in encrypted live-streaming programs.

International police agencies are mobilising. The Virtual Global Taskforce, a partnership of international law enforcement agencies and Interpol, has dedicated 2016 to combatting the live-streaming of child abuse.

Next month, Unicef will launch a campaign to educate young people about the risks of the online world.

The UK’s #WeProtect project, an international alliance to fight online child abuse, has promised £10m to the campaign.